NOVEL VIII.

Anastasio, being in love with a young lady, spent a good part of his fortune, without being able to gain her affections. At the request of his relations he retires to Chiassi, where he sees a lady pursued and slain by a gentleman, and then given to the dogs to be devoured. He invites his friends, along with his mistress, to come and dine with him, when they see the same thing, and she, fearing the like punishment, takes him for her husband.

When Lauretta had made an end, Filomena began thus, by the queen's command: - Most gracious ladies, as pity is a commendable quality in us, in like manner do we find cruelty severely punished by Divine Justice; which, that I may make plain to you all, and afford means to drive it from your hearts, I mean to relate a novel as full of compassion as it is agreeable.

In Ravenna, an ancient city of Romagna, dwelt formerly many persons of quality; amongst the rest was a young gentleman named Anastasio de gli Onesti, who, by the deaths of his father and uncle, was left immensely rich; and being a bachelor, fell in love with one of the daughters of Signor Paolo Traversaro (of a family much superior to his own), and was in hopes, by his assiduous courtship, to gain her affection. But though his endeavours were generous, noble, and praiseworthy, so far were they from succeeding, that, on the contrary, they rathei turned out to his disadvantage; and so cruel, and even savage was the beloved fair one (either her singular beauty or noble descent having made her thur haughty and scornful), that neither he, nor anything that he did, could ever please her. This so afflicted Anastasio, that he was going to lay violent hands upon himself, but, thinking better of it, he frequently had a mind to leave her entirely; or else to hate her, if he could, as much as she had hated him. But this proved a vain design; for he constantly found that the less his hope, the greater always was his love.

The young man persevered then in his love and his extravagant way of life, till his friends all agreed that he was destroying his constitution, as well as wasting his substance; they therefore advised and entreated that he would leave the place, and go and live somewhere else; for, by that means, he might lessen both his love and expense. For some time he made light of this advice, till being very much importuned, and not knowing how to refuse them, he promised to do so; when, making extraordinary preparations, as if he was going a long journey, either into France or Spain, he mounted his horse, and left Ravenna, attended by many of his friends, and went to a place about three miles off, called Chiassi, where he ordered tents and pavilions to be brought, telling those who had accompanied him, that he meant to stay there, but that they might return to Ravenna. There he lived in the most splendid manner, inviting sometimes this company, and sometimes that, both to dine and sup, as he had used to do before.

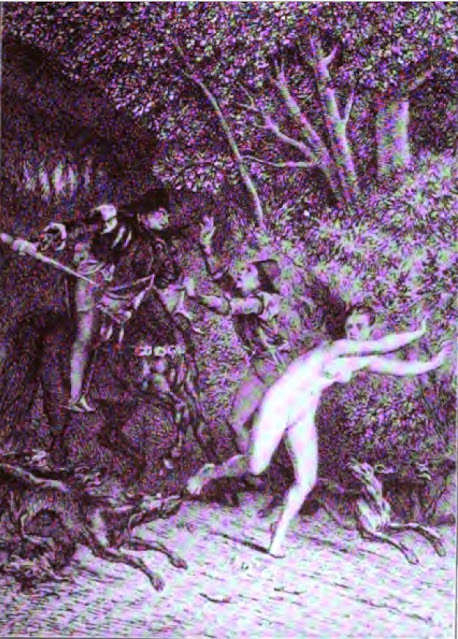

Now it happened in the beginning of May, the season being extremely pleasant, that, thinking of his cruel mistress, he ordered all his attendants to retire, and leave him to his own thoughts; and then he walked along, step by step, and lost in reflection, till he came to a forest of pines. It being then the fifth hour of the day, and he advanced more than half a mile into the grove, without thinking either of his dinner, or anything else but his love; on a sudden he seemed to hear a most grievous lamentation, with the loud shrieks of a woman. This put an end to his meditation, when looking around him, to know what the matter was, he saw come out of a thicket full of briars and thorns, and run towards the place where he was, a most beautiful lady, quite naked, with her flesh all scratched and rent by the bushes, crying terribly, and begging for mercy. In close pursuit of her were two fierce mastiffs, biting and tearing wherever they could lay hold, and behind, upon a black steed, rode a gloomy knight, with a dagger in his hand, loading her with the bitterest imprecations. The sight struck him at once with wonder and consternation, as well as pity for the lady, whom he was desirous to rescue from such trouble and danger, if possible; but finding himself without arms, he tore off a branch of a tree, and went forward with it, to oppose both the dogs and the knight. The knight observing this, called out, afar off", "Anastasio, do not concern yourself; but leave the dogs and me to do by this wicked woman as she has deserved." At these words the dogs laid hold of her, and he coming up to them, dismounted from his horse.

Anastasio then stepped up to him, and said, "I know not who you are, that are acquainted thus with me: but I must tell you, that it is a most villanous action for a man, armed as you are, to pursue a naked woman, and to set dogs upon her also, as if she were a wild beast; be assured that I shall defend her to the utmost of my power."

The knight replied, "I was once your countryman, when you were but a child, and was called Guido de gli Anastagi, at which time I was more enamoured with this woman, than ever you were with Traversaro's daughter; but she treated me so cruelly, and with so much insolence, that I killed myself with this dagger which you now see in my hand, for which I am doomed to eternal punishment. Soon afterwards she, who moreover was rejoiced at my death, died likewise, and for her cruelty, as also for the joy which she expressed at my misery, she is condemned as well as myself; our sentences are for her to flee before me, and for me, who loved her so well, to pursue her as a mortal enemy; and when I overtake her, with this dagger, with which I murdered myself, do I murder her; then I rip her open to the spine, and take out that hard and cold heart, which neither love nor pity could pierce, with all her entrails, and throw them to the dogs; and in a little time (so wills the justice and power of Heaven) she rises, -as though she had never been dead, and renews her miserable flight, whilst we pursue her over again. Every Friday in the year, about this time, do I sacrifice her here, as you see, and on other days in other places, wherever she has thought or done anything against me: and thus being from a lover become her mortal enemy, I am to follow her for years as many as the months she was cruel to me. Let then divine justice take its course, nor offer to oppose what you are no way able to withstand."

Anastasio drew back at these words, terrified to death, and waited to see what the other was going to do. The knight, having made an end of speaking, ran at her with the utmost fury, as she was seized by the dogs, and pulled down upon her knees begging for mercy. Then with his dagger he pierced through her breast, and tore out her heart and her entrails, which the dogs immediately devoured as if half famished. In a little time she rose again, as if nothing had happened, and fled towards the sea, the dogs biting and tearing her all the way; the knight also being remounted, and taking his dagger, pursued her as before, till they soon got out of sight.

Upon seeing these things, Anastasio stood divided betwixt fear and pity, and at length it came into his mind that, as it happened always on a Friday, it might be of particular use.

Returning then to his servants, he sent for some of his friends and relations, and said to them, "You have often importuned me to leave off loving this my enemy, and to contract my expenses; I am ready to do so, provided you grant me one favour, which is this, that next Friday, you engage Paolo Traversaro, his wife and daughter, with all their women, friends and relations to come and dine with me: the reason of my requiring this you will see at that time." This seemed to them but a small matter, and returning to Ravenna they invited those whom he had desired, and though they found it difficult to prevail upon the young lady, yet the others carried her at last along with them. Anastasio had provided a magnificent entertainment under the pines where that spectacle had lately been; and having seated all his company, he contrived that the lady should sit directly opposite to the scene of action. The last course then was no sooner served up, than the lady's shrieks began to be heard. This surprised them all, and they began to inquire what it was, and, as nobody could inform them, they all rose: when immediately they saw the lady, the dogs, and the knight, who were soon amongst them. Great was consequently the clamour, both against the dogs and the knight, and many of them went to the lady's assistance. But the knight made the same harangue to them, that he had done to Anastasio, which terrified and filled them with wonder; then he acted the same part over again, whilst the ladies (there were many of them present who were related to both the knight and lady, and who remembered his love and unhappy death) all lamented as much as if it had happened to themselves.

This tragical affair being ended, and the lady and knight both gone away, they held various discourses together about it; but none seemed so much affected as Anastasio's mistress, who had heard and seen everything distinctly, and was sensible that it concerned her more than any other person, calling to mind her invariable cruelty towards him; so that already she seemed to flee before his wrathful spirit, with the mastiffs at her heels. Such was her terror at this thought, that, turning her hatred into love, she sent that very evening a trusty damsel privately to him, to entreat him in her name to come and see her, for she was ready to fulfil his desires. Anastasio replied, that nothing could be more agreeable to him but that he desired no favour from her but what was consistent with her honour. The lady, who was sensible that it had been always her own fault they were not married, answered, that she was willing; and going herself to her father and mother, she acquainted them with her intention.

This gave them the utmost satisfaction; and the next Sunday the marriage was solemnized with all possible demonstrations of joy. And that spectacle was not attended with this good alone; but all the women of Ravenna were ever after so terrified with it, that they were more ready to listen to, and oblige the men, than ever they had been before.

[We are informed, in a note by the persons employed for the correction of the "Decameron” that this tale is taken, with a variation merely in the names, from a chronicle written by Helinandus, a French monk of the 13th century, which comprises a history of the world, from the creation to the author's time. This story, which seems to be the origin of all retributory spectres, was translated, in 1569, into English verse, by Christopher Tye, under the title of "A Notable Historye of Nastagio and Traversari, no less pitiefull than pleasaunt." It is not impossible that such old translations, now obsolete and forgotten, may have suggested to Dryden's notice those stories of Boccaccio which he has chosen. "Sigismunda and Guiscard, as well as "Cimon and Iphigenia," had appeared in old English rhyme before they received embellishment from his genius. In his "Theodore and Honoria," he has adorned the tale of the spectre huntsman with all the charms of versification. The supernatural agency, as well as the feelings of those present at Nastagio's entertainment, are managed with wonderful skill, and it seems, on the whole, the best executed oi the three novels which he had selected from the "Decameron."

Every one is familiar with Byron's allusion to this story:

“Sweet hour of twilight! - In the solitude

Of the pine forest, and the silent shore

Which bounds Ravenna's immemorial wood.

Rooted where once the Adrian wave flowed o'er.

To where the last Caesarean fortress stood;

Ever green forest! which Boccaccio's lore,

And Dryden's lay made haunted ground to me,

How have I loved that twilight hour and thee !

"The shrill cicalas, people of the pine,

Making their summer lives one ceaseless song.

Where the sole echoes, save my steeds and mine,

And vesper bells, that stole the boughs among.

The spectre huntsman of Onesti's line,

His hell-dogs, and their chace, and the fair throng

Which learn'd from this example not to fly

From a true lover, shadowed my mind's eye." ]