NOVEL V.

Calandrino is in love with a certain damsel; Bruno prepares a charm for her, by virtue of which she follows him, and they are found together by his wife.

Neifile's short novel being concluded, without either too much talk or laughter, the queen ordered Fiammetta to follow, which she did cheerfully in this manner: - There is nothing, be it ever so often repeated, but will please always if mentioned in due time and place. When I consider, therefore, the intent of our meeting, which is only to amuse and divert ourselves whilst we are here, I judge nothing either ill-timed or ill-placed which serves that purpose. So, though we have had much about Calandrino already, yet I will venture to give you another story concerning him; in relating which, were I disposed to vary from the truth, I should carefully have disguised it under very different names; but, as romancing upon these occasions greatly lessens the pleasure of the hearer, I shall report it in its true shape, relying on the reason before assigned.

Niccolo Cornacchini, a fellow citizen of ours, was a very rich man. Amongst his other estates he had one at Camerata, where he built a mansion, and agreed with Bruno and Buffalmacco to paint it; but there being a great deal of work, they took Nello and Calandrino to assist them. As some of the chambers were furnished, and there was an old woman to look after the house, a son of this Niccolo's named Filippo, a gay young gentleman, would frequently bring a mistress thither for a day or two, and then send her away. Amongst the rest that used to come with him, was one Niccolosa, an agreeable and facetious woman enough, who going from her chamber one morning, in a loose, white bedgown, to wash her hands and face at a fountain in the court, it happened that Calandrino was there at the same time, when he made his compliments to her, which she returned with a kind of smile at the oddity of the man. Upon this he began to look wistfully at her, and seeing she was very handsome, he found pretences for staying, yet durst not speak a word. Still her looks seemed to give him encouragement, and the poor fellow became so enamoured, that he had no power to leave the place, till Filippo chanced to call her into the house. Calandrino then returned to his friends in a most piteous taking, which Bruno perceiving, said, "What the devil is the matter with you, that you seem to be in all this trouble?" He replied, "Ah! my friend, if I had any one to assist me, I should do well enough." - "As how?" - "I will tell you," he replied. "The most beautiful woman you ever saw, exceeding even the fairy queen herself, fell in love with me just now as I went to the well." - "Wheugh!", said Bruno, "you must take care it be not Filippo's mistress." - "I believe it is the same," he replied; "for she went away the moment he called her: but why should I mind that." Was she a king's, I would lie with her, if I could" - "Well," quoth Bruno, "I will find out who she is, and if she proves the same, I can tell you in two words what you have to do; for we are well acquainted together: but how shall we manage, that Buffalmacco may know nothing of the matter Ì I can never speak to her but he will be present." - "As to Buffalmacco," said he, "I am in no fear about him; but we must take care of Nello; he is my wife's relation, and would spoil our whole scheme."

Now Bruno knew Niccolosa, very well, and when Calandrino was gone out one day, to get a sight of her, he acquainted Buffalmacco and Nello with the affair, and they agreed together what was to be done. Upon Calandrino's return, therefore, Bruno whispered him, and said, "Have you seen her?" - "Alas! I have, and she has slain me outright."

- "I will go and see," said Bruno, "whether she be the person I mean; if she be, you may leave the whole to me." So he went and told Filippo and Niccolosa what had passed, and laid a plot with them for making sport of the enamoured Calandrino. He then came back, and said, "It is the same, therefore we must be very cautious; for if Filippo should chance to find it out, all the water in the river would never wash off the guilt in his sight. But what shall I say to her on your part?" - "First, you must let her know," said Calandrino, "that she shall have much joy, and pleasure without end, and afterwards that I am her most obedient servant, and so forth. Do you understand?" - "Yes," quoth Bruno, "I do, and you may now trust me to manage for you."

When supper-time arrived, they left their work, and went down into the court, where they found Filippo and his mistress waiting to make themselves merry with the poor man. Calandrino began at once to ogle her in such a manner that a blind man almost must have perceived it; and she encouraged him with all her heart, thinking it capital fun, whilst Filippo pretended to be talking to Buffalmacco and the others, as if he saw nothing of the matter. After some time the painters left the place, to Calandrino's great vexation, and as they were returning to Florence, said Bruno to Calandrino, "I tell you now, that you have made her melt like ice before the sun; do but bring your guitar, and play her a tune, and she will throw herself out of the window to you." - "Do you think so?" - "Most certainly," replied the other. - "Well," quoth Calandrino, "who but myself could have made such a conquest in so short a time? I am not like your young fellows that whine for years together to no manner of purpose. Oh! you would be vastly pleased to hear me play and sing: besides, I am not old, as you suppose. She saw this at once; but I will convince her still better of it if once I get her unto my clutches.

By the Lord I'll please her so that she will run after me as a mother does after her child." - "Oh, you'll touzle her no doubt," said Bruno; "I fancy I see you with those teeth of yours like lutepegs, biting her little vermilion lips, and her cheeks that looks like two roses, and then munching her all over." Calandrino taking all this in earnest, fancied himself at the sport already, and began to sing and dance about as if he would jump out of his skin. The next morning he carried his instrument with him, and diverted them all very much with his minstrelsy; and not a bit could he work, for he was every moment running to the window, and to the door, in hopes to see his charmer. Bruno carried all his messages, and answered them too as from her; and when she was not there, he would bring letters, purposing to give her admirer hopes that she would soon gratify his desires, but that then she was with her relations, and could not see him.

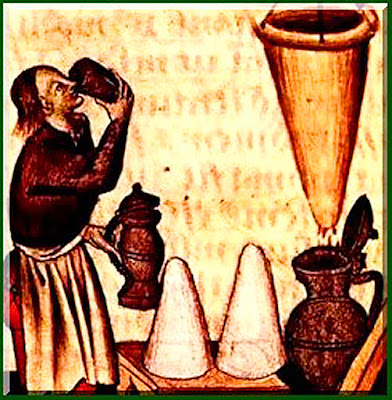

Thus Bruno and Buffalmacco diverted themselves at Calandrino's expense for some time, often getting from him presents to give the lady, such as a comb, a purse, a knife, or such nicknacks, for which Bruno brought him in return counterfeit rings of no value, with which he was vastly delighted. Besides all these things they got many a good treat and presents out of him, that they might be sedulous in attending to his business. The affair had gone on in this manner for two months, when seeing that the work was nearly finished, and imagining that unless he brought his love to a conclusion before that time, he should làave no opportunity of doing it afterwards, he began to be very urgent with Bruno about it. When Niccolosa next came there, Bruno had a talk with her and Filippo. Then he went to Calandrino, and said to him, "Look you, comrade, this lady has made us a thousand promises to no purpose, so that it appears to me as if she only did it to lead us by the nose: my advice, therefore, is, that we make her comply, whether she will or not." - "Odds life! let us do it out of hand," cried Calandrino. - "But," says Bruno, "will your heart serve you to touch her with a certain charm that I shall give you?" - "You need not doubt that." "Then, you must procure me a little virgin-parchment, a living bat, three grains of incense, and a consecrated candle." All that night was Calandrino employed in catching a bat, which at length he brought with the other things to Bruno, who went into a room by himself, scribbled some odd characters upon the parchment, and gave it him, saying, "All you have to do is to touch her with this, and she will do that moment what you would have her. Therefore, if Filippo should go from home, take an opportunity to steal up to her, and having touched her, then go into the barn, which is a most convenient place for your purpose, whither she will follow you, and then you know that you have to do." Calandrino received the charm with great joy, saying, "Let me alone for that." Meanwhile Nello, whom he was most afraid of, and who was as deep as any in the plot, went, by Bruno's direction, to Calandrino's wife, at Florence, and said to her, "Cousin, you have now a fair opportunity to be revenged on your husband, for his beating you the other day without cause: if you let it slip, I will never look upon you more, either as a relation or a friend. He has a mistress, whom he is frequently with, and at this very time they have made an appointment to meet; then pray be a witness to it, and correct him as he deserves." This seemed to her beyond a jest. "Oh, the villain! " She said. "But I will pay him off all old scores." Accordingly, taking her hood, and a woman to bear her company, she went along with him; and when Bruno saw them at a distance, he said to Filippo, 'see, our friends are coming; you know what you have to do." On this, Filippo went where Calandrino and the people were at work, and said,

"Masters, I must go to Florence; you will take care not to be idle when I am away." He then went and hid himself in a place where he might see what passed. As soon as Calandrino thought he was far enough off, he went into the court, where he found the lady all alone. She, well knowing what he meant to do, approached him, looking more than usually gracious. Calandrino touched her with the writing, and immediately moved off, without saying a word, towards the barn, Niccolosa followed him in, and shut the door; then flinging her arms round him, she threw him flat on the straw, fell over him with her hands upon his shoulders, holding him down so fast that he could not kiss her, whilst she made believe to be feasting her eyes with the sight of him. At length she cried out, "O my dear Calandrino! my life! my soul! my only comfort! how long have I desired to have thee in this manner?" He, unable to move, said, "My dearest joy! do let me have one kiss." - "My jewel," replied she, "thou art in too much haste; let me satisfy myself first with gazing upon thee." Bruno, Buffalmacco, and Filippo, heard and saw all this; and just as he was striving to get a kiss from her, up comes Nello along with the wife, and cries, "I vow to God they are together." Monna Tessa, in her rage, burst open the door, and beheld Niccolosa astride of Calandrino, until on the entrance of intruders she left her spark, and went to Filippo; whilst the wife ran and scratched Calandrino's face all over, and tore out his hair, screaming at him, "You poor pitiful rascal, to dare to serve me in this manner! You old villain! What! have you not enough to do at home? A fine fellow, truly, to pretend to a mistress, with this old worn-out carcase! and she as fine a lady, to take up with such a precious thing as you are!" Calandrino was confounded to that degree, that he made no defence; so she beat him as she pleased, till at length he humbly begged her not to make that clamour, unless she had a mind to have him murdered, for that the lady was no less a person than the wife of the master of the house.

"A plague confound her," she said, "be she who she will." Bruno and Buffalmacco, who, with Filippo and Niccolosa, had been laughing heartily at what passed, came in upon them now, as though they had been drawn thither by the noise. When, with much ado, they had pacified Monna Tessa, they persuaded Calandrino to go home, and come back no more, for fear Filippo should do him a mischief. So he went to Florence, miserably scratched and beaten, without having the heart ever to return; but plagued with the perpetual reproaches of his wife, he let his hot love grow cold, after having afforded great matter for diversion to his friends, to Niccolosa, and to Filippo.