NOVEL IX.

Saladin, disguising himself like a merchant, is generously entertained by Signor Torello, who, going upon an expedition to the Holy Land, allowed his wife a certain time to marry again. In the meantime he is taken prisoner, and being employed to look after the hawks, is recognised by the Soldan, who shows him great respect. Afterwards Torello falls sick, and is conveyed by magic art, in one night, to Pavia, at the very time that his wife was to have been married; when he makes himself known to her, and returns with her home.

Filomena had now concluded her story, and Titus's gratitude having been much applauded, the king tegan in this manner: - Most certainly, ladies, Filomena is in the right as to what she has said upon friendship; and it was with reason she complained, last of all, of its being in such little esteem with mankind: and, had we met here to correct or reprove the vices of the age, I could proceed in a fluent harangue to the same purpose; but, as that is foreign to our design, I intend to relate, in a long but pleasant novel, one of the many generous actions of Saladin; to the end, that if, through our imperfections, we cannot attain the friendship of any one, we should yet make it a pleasure to oblige, in hopes that a reward may ensue some time or other.

I say, therefore, that in the reign of the Emperor Frederick the First, a general crusade was undertaken by all the Christian princes for the recovery of the Holy Land: which design of theirs coming first to the ears of Saladin, a most renowned prince, then soldan of Babylon, he resolved to go in person to see what preparations were making against him, in order to provide the better for his own defence. So, settling all his affairs in Egypt, and taking with him two of his most sage and principal nobles, and three servants only, he set forwards in the habit of a merchant, as if he was going on a pilgrimage. After travelling over many Christian countries, and riding through Lombardy, in order to pass the mountains, it happened, towards the evening, that, between Pavia and Milan, he met with a gentleman, named Torello d'Istria, who was going with his hawks, hounds, and servants to a country-house that he had on the river Tesino.

Torello, upon seeing them, supposed that they were strangers of some quality, and as such was desirous of showing them respect. Saladin, therefore, having asked one of the servants how far it was to Pavia, and if they could get there time enough to be admitted. Torello would not let the servant reply, but answered himself, "Gentlemen, it is impossible for you to reach Pavia now before the gates are shut."

- "Then," quoth Saladin, "please to inform us, as we are strangers, where we may meet with the best entertainment." Torello replied, "That I will do with all my heart; I was just going to send one of my fellows to a place near Pavia, upon some particular business; he shall go with you, and bring you to a place where you will be accommodated well enough." So, taking one of the most discreet of his men aside, and having told him what he should do, he sent him along with them, whilst he made the best of his way to his own house, where he had as elegant a supper provided for them as was possible within so short a time, and the tables all spread in the garden; and when he had done this he went to the door to wait fop his guests. The servant rode chatting along with them, leading them by round-about ways, till at last, without their suspecting it, he brought them to his master's house. As soon as Torello saw them, he advanced pleasantly, saying, "Gentlemen, you are most heartily welcome.” Saladin, who was a very shrewd person, perceived that the knight was doubtful whether they would have accepted his invitation had he asked them to go with him home, and that he had contrived this stratagem not to be denied the pleasure of entertaining them. So he returned his compliment, and said, "If it was possible for one person to complain of another's courtesy, we should have cause to blame yours, which, not to mention the hinderance of our journey, compelled us, without deserving your notice otherwise than by a casual salutation, to accept of such great favours as these." Torello, being both wise and eloquent, replied, "Gentlemen, it is but poor respect you receive from me, compared to what you deserve, so far as I can judge by your countenances; but, in truth, there was no convenient place out of Pavia that you could possibly lie at; then pray take it not amiss that you have stepped a little out of your way to be something less incommoded." As he said this, the servants were all at hand to take their horses; so they alighted, and were shown into rooms prepared for them, where they had their boots pulled off, were refreshed with a glass of wine, and fell into an agreeable discourse together afterwards till supper-time.

Now Saladin and his people all spoke Latin extremely well, so that they were easily understood by each other, and Torello seemed, in their judgment, to be the most gracious, accomplished gentleman, and one that talked the best of any they had ever met with. On the other hand, Torello also judged them to be people of great rank and figure, and much beyond what he at first apprehended; for which reason he was extremely concerned that he could not then have an entertainment and guests suitable. But for this he resolved to make amends the following day; and having instructed one of his servants what he would have done, he sent to Pavia, which was near at hand, and by a way where no gate was locked, to his wife, who was a lady of great sense and magnanimity. Afterwards, taking his guests into the garden, he courteously demanded of them who they were. Saladin replied, "We are merchants from Cyprus, and are going upon our affairs to Paris." - "Would to heaven, then," said Torello, "that our country produced such gentry as I see Cyprus does merchants!" So they fell from one discourse to another till the hour for supping, when they seated themselves just as they pleased, and a supper, entirely unexpected, was served up with great elegance and order. In some little time, after the tables were removed, Torello, supposing they might be weary, had them conducted to their chambers, where most sumptuous beds were prepared for them, and he in like manner went to take his rest.

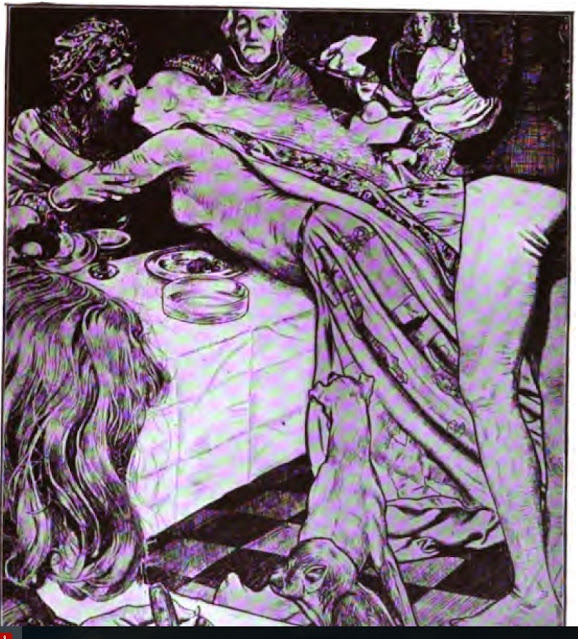

The servant that was sent to Pavia delivered his message to the lady, who, not with a feminine disposition, but a soul truly loyal, got together great numbers of the friends and servants of Torello, and had everything provided to make a feast indeed, sending through the city by torchlight, to invite most of the nobility, and setting forth all the rooms with rich furniture of cloth of gold, fine tapestry, velvets, etc., according to his directions. In the morning the gentlemen arose, and mounted their horses, along with Torello, who ordered out his hawks, and carried them to a neighbouring lake, where he showed them two or three fair flights; but Saladin requesting somebody to direct him to the best inn in Pavia, Torello said, "That I will do, because I have business there. So they were satisfied, and rode on along with him, arriving there about the third hour of the day. And whilst they supposed that he would carry them to thè best inn, he brought them directly to his own house, where were about fifty of the principal persons of the city ready to receive them. Saladin and his friends perceiving this, readily guessed how the matter was, and they said, "sir, this is not what we desired; you did enough for us last night, and more than we could have wished; you might now, therefore, very well let us pursue our journey." He made answer, "Gentlemen, last night I was obliged to fortune, which surprised you upon the road in such manner that you were necessitated to take up with my little mansion; but now I shall be indebted to you, and these noble persons all around equally with me, if, out of your great courtesy, you will not refuse the favour of dining with me," Thus they were prevailed upon, and they alighted from their horses, when they were welcomed by the company with great joy and respect, and conducted into several apartments most richly set for their reception, where laying aside their riding-dresses, and taking some refreshment, they then made their appearance in the grand hall. After washing their hands they sat down all in order, when such a prodigious entertainment was served up, that if the emperor himself had been present, he could not have been more sumptuously regaled. Even Saladin himself, and his friends, who were people of figure, and accustomed to everything of grandeur, could not help being astonished, having regard to the rank of the person whom they knew to be only a private gentleman. When dinner was over, and they had discoursed a little together, the Pavian gentry all withdrew to repose themselves, the weather being extremely hot; and Torello, being left with his three guests, showed them into a drawing-room, where, that nothing which he valued might be left unseen by them, he sent for his lady. She, therefore, being a person of extraordinary beauty, and most sumptuously attired, was speedily introduced between her two little sons, who seemed like angels, when she very modestly and genteelly saluted them. At her coming, they arose, and received her with great deference and respect, seating her down by them, and taking great notice of the children. In a little time, after some discourse together, when Torello was gone out of the room, she, in a modest and graceful manner, began to inquire of them whence they came, and whither they were going. To which they returned the same answer they had given to Torello. "Then," said she, very pleasantly "I see, gentlemen, that my poor design may be acceptable; I beg, then, as a particular favour, that you will not think lightly of a very small present which I mean to offer you; but considering that women give little things, according to their slender abilities, that you will accept it, more out of respect to the good intention of the donor, than the real value of the present. So she ordered two robes to be brought for each, the one lined with taffeta, and the other with fur, not so much becoming a citizen or a merchant as a great lord; and three doublets of sarsnet, with the same of linen, saying, "Gentlemen, pray accept of these things: I clothe you as I do my husband: and, for the rest, considering that you are a great way from your wives, that you have come a long journey, and have far yet to go, they may be of service though of small value, especially as you merchants love always to be genteel and neat." They were greatly surprised, seeing plainly that Signor Torello would allow no part of his respect to be wanting, doubting likewise, when they came to see the richness of the presents, whether they were not discovered. At length one of them said, "Madam, these are very great things, and such as we ought not to accept, unless you force them upon us; in which case we must comply." Her husband now returned, when she took her leave, and went and made suitable presents to their servants.

Torello, with much entreaty, prevailed upon the strangers to stay there all that day: therefore, after taking a little sleep, they put on those robes, and took a ride with him round the city, and at their return were nobly entertained with a great deal of good company at supper. At due time they went to bed, and when they arose in the morning, instead of their wearied steeds, they found three strong, handsome, fresh ones, with new serviceable horses also for their servants; which when Saladin saw, he turned to his friends, and said, "I vow to Heaven, a more complete, courteous, or a more understanding gentleman, I never met with anywhere; and if the Christian kings be in their degree like to him, the soldan of Babylon would never be able to stand against one, much less so many as are now preparing to invade us." Knowing well that it would be in vain to refuse the horses, after returning all due thanks, he and his attendants mounted, and Torello, with a great number of his friends, went with them a considerable distance from the city: and, though Saladin was grieved to separate from Torello, such was the regard he had conceived for him, yet, being constrained to depart, he begged he would return. He, yet loath to leave them, replied, "Gentlemen, I will dp so, as it is your desire; but this I must tell you, I know not who you are, nor do I seek to be informed any farther than you desire I should; but, be you who you may, you shall never make me believe that you are merchants, and so I commend you to Providence." - Saladin then took leave of all the company, and to Torello he said, "Sir, we may chance to show you some of our merchandise, and so convince you; but, in the meantime, fare you well." Thus Saladin departed, and his companions, with a firm resolution, in case he lived, and the approaching war did not prevent it, to show no less respect and honour to Signor Torello than he had received from him; and talking much of him, his lady, and everything that he had said and done, he commended all, to the greatest degree imaginable. At length, after Saladin had travelled over the west, not without great labour and fatigue, he embarked on board a ship for Alexandria; and being fully informed as to every particular, he prepared for a most vigorous defence.

Signor Torello returned to Pavia, full of conjectures who these three people might be, in which, however, he was far from the truth. But the time was now drawing nigh for the march of the forces, and great preparations being made everywhere. Torello, notwithstanding the prayers and tears of his lady, resolved to go, and having everything in readiness, and being about to mount his horse, he said to her, "My dear, you see I am going upon this expedition, as well for the glory of my body as the safety of my soul: I commend my honour and everything else to your care; and, as my departure is now certain, but my return, by reason of a thousand accidents which may happen, uncertain, I request, therefore, this one favour, that, happen what will to me, if you have no certain account of my being alive, you will only wait a year, a month, and a day, without marrying again, reckoning from the day of my leaving you." The lady, who wept exceedingly, thus replied: "My dear husband, I know not how I shall be able to bear the grief in which you leave me involved for your going from me: but, if I should outlive it, and anything happen amiss to you, you may live and die assured, that I shall live and die the wife of Torello, and of his memory." He then said, "I make not the least doubt but that what you promise will be performed, as far as lies in your power; but you are young, beautiful, and well descended, and your virtues so universally known, that I am afraid, should there be the least suspicion of my death, that many great lords and noble personages would come, and demand you of your brethren and other relations, from whose most urgent solicitations you could never defend yourself, however you might be disposed, and so you would be compelled to give way. It is, then, for this reason, that I would tie you down to that time, and not for a moment longer." The lady said, "I will do all in my power with regard to ray promise; but should I ever think of acting otherwise, yet your injunction I will steadily abide by. Heaven grant, however, that I see you long before that time! "Here she embraced him, shedding abundance of tears, and taking a ring from her fìnger, gave it him, and said, "If I should chance to die before your return, remember me always when you look upon this." He received it, and, bidding every one farewell, mounted his horse and rode away, with a handsome retinue, for Genoa.

At that port they all embarked, and soon arrived at Acre, when they joined the Christian army, which was visited by a mortal pestilence that swept away a great part of the people; and the thin remains of it were, by the dexterity or good fortune of Saladin taken prisoners almost to a man, and distributed into divers cities to be imprisoned, when it was Torello's fortune to be sent to Alexandria. There, being unknown, and fearing lest he should be discovered, he was driven by necessity to undertake the care of hawks, of which he was a great master. By that means he soon fell under the notice of Saladin, who set him at liberty, and made him his falconer. Torello, who went by no other name than that of the Christian, and neither remembered the soldan, nor the soldan him, had all his thoughts at Pavia, and was often contriving how to make his escape, though without success; but some ambassadors from Genoa being come thither to treat with the soldan about the redemption of certain of their countrymen, as they were just upon their departure, he resolved to write to his lady, to let her know he was alive and would make all possible haste home, and to pray her, therefore, to be in daily expectation of his coming; and so he did. He earnestly entreated also, one of the ambassadors, whom he knew, that he would take care those letters came to the hands of the abbot of San Pietro, who was his uncle. Whilst Torello remained in this condition, it happened one day, as Saladin was talking with him about his hawks, that he chanced to laugh, when he made a certain motion with his lips, which Saladin, when he was at his house in Pavia, had taken particular notice of. Upon this he recollected him; and looking steadfastly at him, believed he was the same person. Now leaving his former discourse, he said, "Tell me, Christian, of what country in the west art thou?" - "My lord," replied he, " I am a Lombard, and born in a city called Pavia; but am a poor man, and of no account." When Saladin heard that, he became assured of what he doubted before, saying joyfully to himself, "Providence has now given me an opportunity of showing how acceptable his generosity was to me. So, causing his wardrobe to be set open, he carried him thither, and said, "Take notice. Christian, if there is any one robe amongst these that thou hast ever seen before." Torello soon cast his eye upon that which his lady had given to Saladin, but not imagining it could be the same, he replied, "My lord, I know not one; two there are indeed, which are like what I have worn formerly, and which I gave to three merchants that were at my house." Now Saladin could refrain no longer; but taking him joyfully in his arms, he said, " You are Signor Torello d'Istria, and I am one of the three merchants to whom your lady gave these robes: and now the time is come for me to convince you what my merchandise is, as I said, at my leaving you, might possibly happen."

Torello, at hearing these words, was overwhelmed both with joy and shame: joy, at having had such a guest; and shame, to think how indifferently he had received him. Then said Saladin, "Torello, as Providence has sent you hither, account yourself to be master, and not me. So, after great expressions of joy, he clothed him in royal apparel, and having recommended him to all his principal barons, and spoken highly in his praise, he commanded them to show him the same respect and honour as they would himself, if they expected any favour at his hands; which, accordingly, they all observed, especially the two lords who had accompanied Saladin at his house.

The great pitch of grandeur and glory, to which Torello saw himself so suddenly advanced, had made him forgetful of his affairs in Lombardy, especially as he was in hopes that his letters had been conveyed safe to his uncle. Now there was among the Christians, on the day they were surprised by Saladin, a gentleman of small esteem, dead and buried, called Torello di Dignes; consequently, as Torello d'Istria was universally known through the whole army, on account of his nobility, whoever heard that Torello was dead, concluded it was he of Istria, and not of Dignes; and their being all taken prisoners immediately upon that event, prevented people's being undeceived; so that many Italians returned home with the news, and some were daring enough to affirm that they had seen him dead, and were present at his interment. This occasioned great grief both to his wife and his relations, as also to every one that knew him. It would be tedious to set forth the lady's trouble and affliction, who, after wearing out some months in mourning, and beginning now to be a little comforted, was much pressed by her brethren and relations to marry again, seeing she was courted by divers great lords of Lombardy. She several times, with tears, withstood their solicitations, till, being over-importuned, she consented at last, provided they would let her wait the time prescribed by Torello.

Things proceeding thus at Pavia, and there wanting only eight days for her taking a second husband, it happened one day that Torello met with one cf the people whom he had seen go on board with the Genoese ambassadors, and inquiring of him what sort of a voyage they had, and when they arrived at Genoa, the other replied, "sir, they had a very bad one, as we understood at Crete, whither I was bound; for, as they came near to Sicily, a strong north wind arose, which drove them upon the sands of Barbary, so that every soul of them perished, and amongst the rest two of my brethren were lost." Torello gave credit to this account, which indeed was very true, and calling to mind that the limited time was near expiring, supposing likewise that no tidings had come to Pavia concerning him, he took it for granted that she would be married again, and laid it so much to heart, that he began to loathe his food, and was brought to death's door; which, when Saladin understood, who had a great affection for him, he came to visit him, and learning, after great importunity, the cause of his disorder, he reproved him for not acquainting him with it sooner, desiring him, nevertheless, to be easy, and promising that he should be at Pavia within the time, and he told him in what manner. Torello gave credit to these words, hearing that it was possible, and had been often done, and he began to take heart, and to press Saladin about it; who, therefore had recourse to a necromancer, whose skill he had made trial of, desiring he would convey Torello upon a bed to Pavia in one night's time. The necromancer promised it should be done, but said it would be more convenient for him to be thrown into a sleep. This having been concerted, Saladin returned to Torello, and found him bent upon being at Pavia, if possible, within the time, otherwise wishing to die; when he said to him, "Torello, if you have that prodigious value for your lady, and are in such concern lest she should be given away to another, heaven knows my heart, I can in no way blame you for it; because, of all the women I ever saw, her address and behaviour, setting beauty aside, which is only a fading flower, are most to be commended and esteemed. I should have been glad, as fortune has sent you hither, that what time we have to live we might have reigned together in these our kingdoms. But as I am not likely to have this favour, and you seem resolved to go to Pavia in due time, or else to die, I could greatly have wished to have known it early enough, that I might have sent you home with that state and equipage which your virtue justly requires. But as this did not happen, and you are desirous of being instantly there, I will take care you shall be conveyed in the manner I related to you." Torello then replied, "My lord, the effects, without the words, have sufficiently made manifest your generous disposition towards me, and which, in that supreme degree, is far beyond my deserts: what you say, living or dying, I shall most assuredly rely upon you. As that, then, is my desire, I beg it may be done immediately, for tomorrow is the last day of my being expected."

This Saladin promised, and resolving to send him away the following night, he had a most beautiful and rich bed put up in his grand hall, made of fine velvet and cloth of gold, according to their custom, over which was a most curious counterpoint, wrought in certain figures, with the largest pearls and other precious stones, supposed to be of immense value, with two noble pillows, suitable to such a bed. When this was done, he ordered Torello to be clothed after the Saracen manner, with the richest and most beautiful robes that were ever seen, and a large turban folded upon his head; and it now growing late, he went with divers of his nobles to the chamber where Torello was, when, sitting down by him, he began to weep and say, "Torello, the hour is now at hand which must divide us, and as I can neither attend you myself, nor cause you to be attended, through the nature of the journey you have to go, which will not admit of it, I must, therefore, take leave of you in your chamber, for which purpose I am now come hither. First, then, I commend you to God's providence, begging you, by the love and friendship existing between us, to be mindful of me always, and, if it be possible, before we finish our lives, that you would settle your affairs in Lombardy, and come once more at least to see me, in order to make some amends for the pleasure which your hasty departure now deprives me of: and till this shall happen, do not think much to visit me by letters, asking whatever favours you please from me, being assured there is no person living whom I would so readily oblige as yourself." Torello could not refrain from tears, and answered in a few words, as well as he could for weeping, that it was impossible the favours he had received should ever be forgotten by him, and that, at a proper time, he would not fail to do what he desired. Saladin then embraced him, and saying, "God be with you! "departed out of the chamber, weeping: the nobles also took their leave, and went with Saladin into the great hall, where the bed was provided. But it now waxing late, and the necromancer desiring despatch, a physician came with a certain draught, and telling him that it was to fortify his spirits, made him drink it off, when he was immediately cast into a profound sleep. He was then, by Saladin's order, laid upon that magnificent bed, on which was set a most beautiful crown, of prodigious value, written upon in such a manner as to show that it was designed by Saladin as a present to Torello's lady. On his finger he put a ring, wherein was a carbuncle, that appeared like a flaming torch, the value of which was not to be estimated. To his side was a sword girt, with such ornaments that the like was scarcely ever seen. About his neck was a kind of solitaire not to be equalled for the value of the pearls and other precious stones, with which it was embellished. And, lastly, on each side were two great basins of gold, full of double ducats, with many strings of pearl, rings, girdles, and other things, too tedious to mention; which were laid all round him. When this was done, he kissed Torello once more, as he lay upon his bed, commanding the necromancer then to use all possible expedition. Instantly the bed, with Torello upon it, was carried away in presence of them all, leaving them in discourse about it, and set down in the church of San Pietro di Pavia, according to his own request. There, in the morning when it rung to matins, he was found fast asleep, with all these jewels and other ornaments, by the sacrist, who, coming into the church with a light in his hand, and seeing that rich bed, was frightened out of his wits, and ran out. - When the abbot and monks saw him in this confusion, they were greatly surprised, and inquired the reason, which the monk told them. "How!" quoth the abbot, "thou art no child or stranger here, to be so easily terrified: let us go and see this bugbear." They then took more lights, and went all together into the church, where they saw this wonderful rich bed, and the knight lying upon it fast asleep. And, as they stood gazing at a distance, and fearful of taking a nearer view, it happened, the virtue of the draught being gone, that Torello awoke, and heaved a deep sigh; at which the monks and abbot all cried out, "Lord have mercy upon us! "and away they ran. Torello now opened his eyes, and looking around him, saw he was where he had desired Saladin to have him conveyed, at which he was extremely satisfied; so raising himself up, and beholding the treasure he had with him, whatever Saladin's generosity seemed to him before, he now thought it greater than ever, as having had more knowledge of it. Nevertheless, without stirring from the place, seeing the monks all run away in that manner, and imagining the reason, he began to call the abbot by name, and to beg of him to entertain no doubts in the affair, for that he was Torello, his nephew. - The abbot, at hearing this, was still more afraid, as he supposed him dead many months before; till, being assured, by good and sufficient reasons, and hearing himself again called upon, he made the sign of the cross, and went to him. Then said Torello, "Father, what are you in doubt about? I am alive, God be thanked, and now returned from beyond sea." The abbot, notwithstanding he had a great beard, and was dressed after the Turkish fashion, soon remembered him; and plucking up some courage, he took him by the hand, and said, "son, you are welcome home. You need not be surprised at my fear, for there was nobody here but was fully persuaded of your death, insomuch that, I must tell you, your lady, Madam Adalieta, overpowered by the prayers and threats of her friends, is now married again, contrary to her own will, and this morning she is to go home to her new husband, and everything is prepared for solemnizing the nuptials."

Torello now rose, and saluted the abbot and all the monks, begging of them to say nothing of his return, till he had dispatched a certain affair. Afterwards, having carried all the jewels and wealth into a place of safety, he related all that had passed to the abbot, who was extremely rejoiced. He then desired to know who that second husband was, and the abbot informed him; when he replied, "I should be glady before she knows of my return, to see how she relishes this wedding: therefore, though it be unusual for the clergy to go to such entertainments, yet, for my sake, I wish you could contrive so that we may both be there." The abbot answered, that he would with all his heart.

When it was daylight, he sent to the bridegroom, to let him know that he and a friend would come together to his wedding. The bridegroom replied that he should be obliged to them for the favour. And when dinner-time came. Torello, in the same habit in which he had arrived, went along with the abbot to the bridegroom's house, where he was wonderfully gazed at, though known by nobody, the abbot giving out that he was going as an ambassador from the Soldan to the King of France. Torello was then seated at a table opposite to his wife, whom he beheld with great pleasure, and thought he saw uneasiness in her looks at these nuptials. She would likewise give a look sometimes towards him, not out of any remembrance she had of him, for that was quite taken away by his great beard, strange dress, and her full persuasion that he was dead. At last, when he thought it a fit time to try if she would remember him, he took the ring in his hand which she had given him at his departure, and calling one of the young men that were in waiting, he said, "Tell the bride, from me, that it is a custom in our country, when any stranger, as I may be, is at such an entertainment as this, for the bride, in token of his being welcome, to send the cup in which she herself drinks, full of wine; when, after the stranger has drunk what he pleases, and covered up the cup, the bride then pledges him with the lest." The youth delivered the message to the lady, who, thinking him to be some great personage, to let him see his company was agreeable, ordered a large golden cup, which she had before her, to be washed, and filled with wine, and to be carried to him. Torello, having put the ring into his mouth, contrived to let it fall into the cup, without any one's perceiving it; and leaving but little wine therein, he covered it up, and sent it to the lady, who received it; and, in compliance with the custom, uncovered and put it to her month, when she saw the ring; and, considering it awhile, and knowing it to be the same she had given her husband, she took it, and began to look attentively at the supposed stranger; when, calling him to mind, like a distracted person, she threw all the tables down before her, crying out, "This is my lord! This is truly Torello?" Then, running to the table where he was sitting, without having regard to anything that was upon it, she cast that down likewise, and clasped her arms about him in such a manner as if she would never sept rate from him more. At last, the company being in some confusion, though for the most part pleased with the return of so worthy a knight, Torello, after requesting silence, gave them a full account of what had befallen him to that hour; concluding that he hoped the gentleman who had married his wife, supposing he was dead, would not be offended, seeing he was alive, that he took her back again. The bridegroom, though he was not a little disappointed, replied freely, and as a friend, that no doubt he might do what he pleased with his own. She consequently gave up the ring and crown, which she had received from her new husband, and put on that ring instead, which she had taken out of the cup, and likewise the crown sent to her by Saladin; and, leaving the bridegroom's house, she went home with all nuptial pomp along with Torello, and his friends and relations, whom his loss rendered disconsolate, and all the citizens likewise, looking upon him as a miracle, went joyfully to see him, and pay him their respects. Part of the jewels Torello gave to him who had been at the expense of the marriage-feast, and part to the abbot, and to divers others; and having signified his happy arrival to Saladin, he remained from that time his friend and faithful servant, living many years afterwards with his most worthy spouse, and continuing more generous and hospitable than ever. This, then, was the end of both their afflictions, and the reward of their most cheerful and ready courtesy. - Many there are that attempt the like, who, though they have the means, do it yet with such an ill grace, as turns rather to their discredit. If, therefore, no credit ensue thence, neither they nor any one else ought to be surprised.