NOVEL VII.

A certain scholar is in love with a widow lady named Helena, who, being enamoured of another person, makes the former wait a whole night for her during the midst of winter, in the snow. In return, he afterwards contrives that she shall stand naked on the top of a tower, in the middle of July, exposed to the sun and all manner of insects.

The company could not help laughing at Calandrino's simplicity, though they thought it too hard for him to lose both the fowls and the pig. The story being ended, the queen ordered Pampinea to begin, which she did in this manner: - It often happens that the mockery which a man intends for another, falls upon his own head, and therefore it is no mark of a person's good sense to take delight in such practices. In our former novels, we have made ourselves very merry with divers tricks that have been put upon people, where no revenge has been taken; but I design to move your compassion for a just return which a certain lady of our city met with, whose jest recoiled upon herself, and to the hazard of her life, being mocked in the same manner; the hearing of which may be of great service to you, as it will be a caution not to do the like; and you will be wise if you attend to it.

There lived, not long since, at Florence, a handsome young lady, of a good family, as well as plentiful fortune, named Helena, who, being left a widow, had chosen to continue so, having found a young gentleman who was quite to her mind, and with whom, by the assistance of her favourite maid, she carried on a very satisfactory intrigue. In the meantime, a young gentleman of our city, whose name was Rinieri, returned from Paris, where be had long studied, not for the sake of retailing his learning by the inch, as many do, but only to know the nature of things, and their causes, as becomes a gentleman. He was much respected in Florence, on account both of his rank and learning, and lived there as became a worthy citizen. But, as it often happens that persons of the most sense and scholarship are the soonest caught in the snares of love, so it fell out with our Rinieri. For, being at a feast one day, he met with this lady, clothed in her weeds, when she seemed to him so full of beauty and sweetness, that he never saw any one to compare to her; and happy he thought the man whom fortune should bless with her as his wife. And casting his eye towards her once and again, and being sensible that great and valuable things are not to be attained without trouble, he resolved to make it his whole care to please her, and to gain her affection if it were possible. The lady, who did not always look upon the ground, but thought full as well of herself as she deserved, throwing her eyes artfully about her, was soon sensible if any one beheld her with pleasure; so she immediately took notice of Rinieri, and said, smiling to herself, "I think I am not come out today in vain, for I seem to have caught a gudgeon." And she would give him now and then a glance from a comer of her eye, to let him see she was pleased with him, thinking that the more admirers she had, of the greater value would her charms be to that person on whom she had bestowed them.

Our scholar now began to lay all his philosophy aside, and turned his thoughts entirely to the lovely widow; and learning where she lived he was continually passing that way, under one pretence or other, thinking thereby to please her; whilst the lady, for the reason before given, seemed gratified by his devotion. By and by he found means of talking to the maid, desiring her interest and intercession with her mistress, so that he might obtain her favour. The maid promised to do her utmost, and forthwith spoke to her lady, who turned Rinieri and his love into extreme derision. "Observe now," she said, "this man is come here to lose the little sense that he went to fetch "from Paris, and he shall have what he looks for. Go, then, and tell him that my love is equally great for him, but that I must have regard to my honour; which, if he is as wise as he would be thought, he will like me the better for." Alas! poor woman, she knew not what it was to try her wit against a scholar! The maid delivered her message, upon which the scholar, being overjoyed, began to press the thing more closely, and to write letters, and send presents, which were all received, though he had no answer in return but what was general; and in this manner he was long kept in suspense.

At last the widow related the whole affair to her lover, and he being a little uneasy and jealous about it, to convince him that his suspicion was ill-grounded, and being much solicited by the scholar, she sent her maid to tell Rinieri, that she had yet had no opportunity to oblige him, since she had made a discovery to him of her love, but that the next day, being Christmas day, she hoped to receive him; bidding him come that evening into her court-yard, and she would meet him there as soon as it was convenient. The scholar, overjoyed at this, failed not to come at the time appointed, when he was put into the court-yard by the maid, and locked up there to wait. Meanwhile the lady had invited her lover to be with her that very night; and after they had supped agreeably together, she let him know what she meant to do, adding, "And now you may see how great my regard is for you, as well as for him of whom you have been so foolishly jealous." The lover listened eagerly to this, being desirous of seeing some proof of that for which he had only her word. A great snow had fallen the day before, and everything was covered with it, which made our scholar feel colder than he could have wished; however, he bore it with great patience, expecting soon to have amends made him. - After a little while the lady said to her lover, "Let us go into the chamber, and see out of the window what this man is doing, of whom you were jealous, and what answers he will make to the maid, whom I have sent to talk with him. So they went up stairs, and looking out, without being seen, they heard the girl saying to him, "sir, my lady is exceedingly uneasy, for one of her brothers has happened to come to see her this evening, and they have had a great deal to talk together, and he would needs sup with her, nor is he yet gone away; but I believe he will not stay long, and for that reason she has not been able to come to you, but will make what haste she can; and she hopes you will not take it ill, that you are forced to wait thus." The scholar supposing it to be really so, replied, "Pray, tell your mistress to have no care for me, till she can conveniently be with me, but that I hope she will be as speedily as possible." The girl then left him, and went to bed.

"Well," said the lady to her lover, "what think you now? Can you imagine, if I had that love for him which you seemed to apprehend, that I would let him stay there to be frozen to death?" Thus they talked and laughed together about the poor scholar, while he was forced to walk backwards and forwards in the court, to keep himself warm, without having anything to sit down upon, or the least shelter from the weather. He cursed the brother's long stay, and expected that everything he heard was the door opening for him - but expected in vain. About midnight, Helena again said to her lover, "Well, my dear, what is your opinion now of our scholar? Whether do you think his sense or my love the greater at this time? Surely you will let me hear no more of that jealousy which you seemed to express yesterday." - "Heart of my body," replied the lover, "I know that as you are my treasure, my joy, and my only hope, so am I yours." - "Then give me a thousand kisses to show that you speak the truth." Embraces followed of course, and after some time so spent, she said again, "We will take another peep, and see whether that fire be extinct or not, which this new lover of mine used to write me word had well nigh consumed him." They got up, and going again to the window, they saw Rinieri dancing a jig in the snow, to the chattering of his teeth. "You see now," she said, "that I can make people dance, without the music either of fiddles or bagpipes; but let us go to the door, and do you stand still, and listen whilst I speak to him; perhaps we may have as much diversion in that manner, as by seeing him." She went softly, and called to him through the key-hole, which made the scholar rejoice exceedingly, supposing that he was to be admitted. Stepping to the door, "I am here, Madam," he said, "for Heaven's sake open the door, for I am ready to die with cold." “surely," she replied, "you can never be so starved with this little snow; it is much colder at Paris: but I can by no means let you in yet; for this unlucky brother of mine, who came to sup with me last night, is yet with me; but he will go soon, and then I will come directly and open the door: it was with great difficulty that I could get away from him now, to come to you, and beg you would not be uneasy at waiting so long."

- "Let me beg of you, then," said he, "but to open the door, that I may stand only under cover, for it snows fast, and afterwards I will wait as long as you please." - "Alas! my dear love, the door makes such a noise always in opening, that my brother will hear it; but I will go and bid him depart first, and then open it." - "Make what haste you can," said the scholar, "and pray have a good fire ready against I come in, for I am so benumbed, that I have almost lost all sense of feeling." - "Impossible! if that be true which you have so often written to me, that you were all on fire with love; but I see now that you were jesting all the time. Have a good heart, however, for I am going."

The poor scholar who seemed transformed into a stork, his teeth chattered so, now perceiving that he was hoaxed, made several attempts to open the door, and looked round to see if there was any other way to get out; but not finding any, he began to curse the inclemency of the weather, the lady's cruelty, the long nights, and his own folly. Exasperated to the last degree, his ardent love was now changed into as rank a hatred, whilst he busied himself in contriving various methods of revenge, which he longed for as passionately as he had before desired to be with the lady. The long night at last wore away, and when daylight began to appear, the maid, as she had before been instructed, came down into the court, and said, with a show of pity, "It was very unlucky, sir, that person's coming to our house last night, for he has given us a world of trouble, and you are, in consequence, almost frozen to death. But have a little patience; for what could not be done then may be brought to pass another time. I know very well that nothing could have given my lady so much uneasiness." The scholar, who with all his wrath was wise enough to know that threats serve only as armour for the enemy, kept his resentment within his own breast, and, without showing himself the least disturbed, said in a low voice, for he was so hoarse he could hardly speak, "In truth, I never had a worse night in my life; but I know very well that your lady is not at all to blame, because she came down to me with a great deal of humanity, to excuse herself, and comfort me. Besides, as you say, what could not be now, may be another time. Farewell, and pray give my service to her," He then made what shift he could to crawl home, threw himself upon the bed to rest, and when he awoke he found he had lost the use both of his hands and feet. He therefore sent for physicians, and acquainted them with the cause of his illness, but it was a very long time before they could succeed in supplying his shrunken nerves, so that he could stir his limbs; and had it not been for his youth, and the warm weather coming on soon after, he could hardly ever have got over it. At last he was sound and well again, and keeping his enmity to himself, he pretended to be as much in love with the widow as ever; and fortune furnished him after a while with an opportunity for satisfying his revenge.

Helena's lover had taken a fancy to another lady, and turned herself adrift, which gave her such concern, that she seemed to pine away. Her maid, who was much grieved finding no way to comfort her for the loss of her spark, and seeing the scholar pass that way sometimes, had a foolish notion come into her head, that he might be able to bring back the truant by some magical operation, of which he was said to be a great master; and she acquainted her mistress with her thoughts. The foolish lady, never reflecting that had Rinieri been really a proficient in magic he would have employed it on his own account, listened to the girl, and bade her learn from him whether he was willing to oblige her, promising anything in return that he should desire. The maid delivered the message, and the scholar (saying with great joy to himself, "Thank Heaven, the time is now come for me to be revenged of this woman for the injury she did me in return for my great love") replied, "Tell your mistress that she need give herself no trouble, for were her lover in the Indies, I would bring him back to ask her pardon. How this is to be done I will impart to her as soon as she pleases; and so pray acquaint her from me with my service."

The girl reported what he said, and it was settled that they should meet in Santa Lucia del Prato. Accordingly, they came thither, and had much conversation by themselves; and the widow forgetting how he had been served by her, acquainted him with the whole affair, and desired his assistance. The scholar then said, "Madam, amongst other things that I studied at Paris was the black art, in which I made a great progress; but, as it is a sinful practice, I had made a resolution never to follow it, either for myself or any other person; but in truth I love you so much, that I am unable to refuse either that or anything else which you may require from me; and so if I must go to the devil for this, why then I am ready to do so since such is your pleasure. I must remind you however, that it is a more troublesome operation than you may imagine, either to bring a man back to love a woman, or a woman to love a man; for it is to be done only by the person concerned, who should have a great presence of mind; for all must be done in the night, in a solitary place, and nobody present; conditions which I do not know whether you will be able to conform to." The lady, more amorous than wise, replied, "My love is such, that I would undertake anything to win back him who has abandoned me so wrongfully; only tell me in what I must show that presence of mind you speak of." "Madam," said the scholar, "I must make an image of tin in his name whom you wish to have yours, which I shall send to you; and immediately, whilst the moon is in the decline, you must, after your first sleep, bathe seven times with it in the river; after which you must go, still naked, into some high tree, or upon some uninhabited house-top, and, turning to the north, with the image in your hand, repeat seven times certain words, which I shall give you in writing; and then two damsels, the most beautiful that ever you saw, will appear to you, graciously demanding what service you have for them to do, which you may safely tell them, taking care not to name one person for another. They will then leave you, and you may go afterwards and dress yourself, and return home, being assured that before midnight your lover will come with tears in his eyes to beg your pardon, and from that time he will never forsake you more." The lady, hearing this story, began to think she had already recovered her lover, and replied, "Never fear, I can do all this very well, having the most convenient place for the purpose that can be; for there is a farm of mine close to the river Arno, and as it is now the month of July, the bathing will be very pleasant. And now I remember, there is an uninhabited tower in a lonely place not far off, where the shepherds climb up sometimes by help of a ladder, to look for their strayed cattle; there I can do what you have enjoined me."

The scholar, who knew perfectly both the farm and the tower, answered, "Madam, I never was in that country, and therefore am unacquainted with the farm and tower you mention; but if it be as you say, there cannot be a more convenient spot in the world.

- Well, then, at a proper time I will send the image, and the words you are to repeat; but I entreat you, when your point is secured, and you find how well I have served you, that you will be mindful of me in the promise you have made me." The lady assured him she would do so without fail, and so took leave of him, and went home.

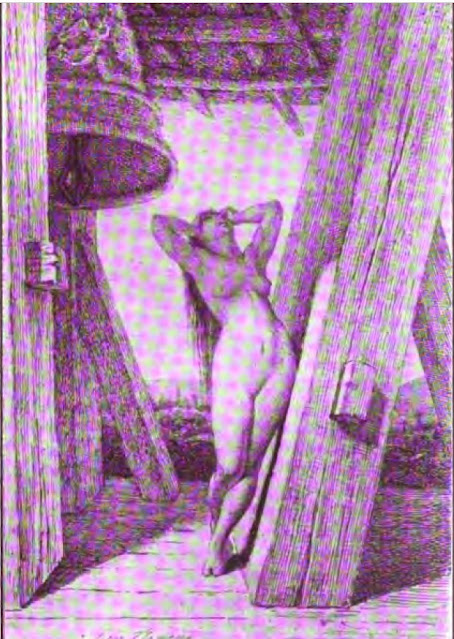

The scholar now concluding that his scheme had taken effect, had an image made, wrote out some rigmarole by way of charm, and sent it to the widow, letting her know that the thing must be done the following night; and then he went privately with one servant to a friend's house which was near, to be ready for what he had designed. The widow went with her maid to her farm, where, pretending to go to bed, and having sent her maid to sleep, she went in the middle of the night to the river side, close to the tower, and looking round to see that nobody was near, she stripped, hid her clothes under a bush, bathed herself seven times with the image, and then went naked to the tower with the image in her hand. The scholar had previously hid himself along with his servant in the sallows near the place, and watched all the lady's movements. When he saw her pass close to him in that manner, admiring the extraordinary beauty of her person, and thinking what it would be in a little while, he began somewhat to relent. Then a sudden tempest of desire assailed him, and he could hardly resist the temptation to rush out from his ambush, and revel in such loveliness. But when he called to mind her unparalleled inhumanity towards him, and what he had suffered, there was an end of pity and desire, and he resolved to put his purpose in execution. So she mounted to the top of the tower, and having turned to the north, began to say the words which he had given her to repeat, whilst he went softly after her, and took away the ladder, waiting afterwards to see what she would say and do.

She had now said the words over seven times, and was expecting the two damsels to come; but the whole night passed away; it was cooler than was by any means agreeable, and daylight began to appear, but no damsels. Weary and vexed at her disappointment, she said to herself, "I begin to fear he had a mind I should pass such a night as I occasioned him to have; but, if that was his intention, he has made a mistake, for the nights are not one-third part so long now as they were then, and besides the cold was infinitely greater at that time." She then determined to come down before it should be broad daylight; but, looking for the ladder, she perceived it was taken away. Upon this her heart failed her, and she fell down in a swoon. As soon as she came to herself, she began to lament bitterly, and (well knowing that it was the scholar's doing) to blame herself for giving him the provocation, as well as for putting herself into his power afterwards. Looking everywhere then to see if there was any other way to come down, and finding none, she renewed her lamentations, saying to herself, "Unhappy wretch! what will your brothers, relations, and all the people of Florence say, when it shall be known that you were found here naked? Your character will be quite lost; and say what you will in your own vindication, the scholar will contradict it. Miserable woman! to lose both your honour and your lover at the same time!" Here her grief was such, that she thought of throwing herself down headlong; but as the sun was now rising she got to one corner of the wall to see if she could discover any shepherd's boy to send for her maid, when it happened that the scholar, who had been taking a nap upon the grass, awoke and saw her, and she him. ""Good morrow, madam," he said, "are the damsels come yet?" At this she fell crying most bitterly, and desired he would come under the tower, that they might have some talk together. He readily obliged her in that, whilst she, lying down with only her head appearing above the battlements, began to weep and say, "sir, if I caused you to have a bad night, you are sufficiently revenged; for, though it is in July, yet I have been just starved to death, as I am naked; not to mention my grief for the trick I put upon you, and for my own folly in believing you, that I have almost cried my eyes out of my head. Therefore I entreat you, not out of any regard to me, for none is due from you; but for your own sake, as you are a gentleman, that you would esteem what you have already made me suffer a sufficient revenge, and that you would order my clothes to be brought, and let me come down; nor offer to take that away from me which it is not in your power to restore; I mean my honour. For if I denied you my company one night, you may have it as many nights as you please in return for that one. Let this, therefore, suffice, and, like a man of worth, think it enough that you have had me in your power; nor set your wit against a woman's. Where is the glory in an eagle's vanquishing a dove? Then for Heaven's sake, and your own honour, show me some pity!"

The scholar found himself alternately influenced by two different motives; one while he was moved with compassion to see her in that distress; but revenge and fury at length gained the superiority, and he replied as follows: - "Madam, if my prayers (though unattended with tears, and such soothing expressions as yours) could have procured only a little shelter for me the night that I was dying in your court, all covered with snow, I could, in that case, easily harken now to what you have to say. But you may remember that you were then with your gallant, entertaining him with my sufferings; let him come, and bring your clothes, and the ladder; for he will be the best guardian of your honour, who has so often had it in his keeping. Why do you not call upon him, then?

It is his business more than any other person's; and if he do not succour you, whom will he regard? You may now see whether your love for him, or your great cleverness, is able to deliver you from my folly; as you were pleased to make a doubt whether that folly or your love for him was greater. And concerning the offer of your person, I desire it not, neither could you withhold it from me if I did. No, keep it all for your lover; for my own part, I have had enough of one night. You think to cajole me, by speaking of my great worth and gentility, and would have me believe that I shall lessen myself by this usage of you. But your flattery shall never blind my understanding, as your fair promises once did; I now know myself, and can say, that I never learnt so much all the time I was at Paris, as you taught me in one night. But, supposing even that I were disposed to be generous, you are no proper object. Amongst savage beasts, as you are, the end of vengeance is death; but with men, indeed, what you say should avail. Therefore, although I am no eagle, yet knowing you to be no dove, but rather a venomous serpent, I shall persecute you with all my might, as an old enemy; though what I do cannot be called revenge, so properly as chastisement; for revenge ought not to exceed the offence given, whereas, considering how I was served by you, were I to take away your life, this would not be equal to it, nor even the lives of a hundred more such women as yourself. For what the devil are you better (setting aside a little beauty, which a few years will take away from you) than the paltriest chamber-maid? And yet, no thanks to you, that the life of a worthy gentleman was not lost, as you were pleased just now to call me, a life which may be of greater service to the world than a hundred thousand such as yours could ever be whilst the world endures. Learn then what it is to mock and abuse people of understanding, and scholars, and be wiser for the time to come, if you happen to escape. But if you have such a desire to come down, why do you not throw yourself to the ground? By breaking your neck, if it please heaven, you may at once escape the punishment which you seem to undergo, and make me the happiest man in the world. So I have nothing more to say to you, but that I have showed you the way up to this tower; do you find a way, if you can, to come down as readily as you could insult me."

All the while the scholar was speaking, was she weeping, while the time kept going on, and the sun rose higher and higher. And when he had made an end, she said, "Ah! cruel man! if that unhappy night still galls you, and my crime appears so heinous, that neither my youth, my tears, nor my humblest entreaties, can move you, yet let this last act of mine alone have some weight to lessen the force of your severity: consider how I put entire confidence in you, and intrusted you with my most secret designs, for without that you would never have had it in your power to revenge yourself of me, as you so much desired. Away, then, with all this fury, and pardon me this time; I am ready, if you will forgive me, and set me at liberty, to abandon that unworthy young man, and have you only for my lover and my lord. And though you make light of my beauty, esteeming it trifling and transitory, yet it is what other young gentlemen would love and value, and you do not think otherwise. And, notwithstanding this cruel treatment, I can never think you would wish to see me dash my brains out before your face, when I was once so agreeable to you. For Heaven's sake, therefore, show me some pity; the sun now waxes warm, and is as troublesome as the coldness of the night."

The scholar, who held her in talk only for his diversion, replied, "Madam, the confidence you reposed in me was out of no regard you had for me, but only to regain your lover; and you are mistaken if you think I had no other convenient way to come at my revenge: I had a thousand others, and had laid a thousand different snares to entrap you; so that, if this had not happened, I must necessarily have taken you in some other; nor was there any one but would have been attended with as much shame and punishment to you as this. I have made choice of it, therefore, not because you gave me the opportunity, but that I might gain my end the sooner. And though they had all failed, yet had I my pen left, with which I would have so mauled you, that you should have wished a thousand times a day that you had never been born. The force of satire is much greater than they are sensible of, on whom it was never tried. I swear solemnly, then, that I would have written such things of you, that you should have pulled your very eyes out for vexation. As to the offer of your love, that is needless: let him take you, if he will, to whom you more properly belong, and whom I now love, for what he has done to you, as much as before I hated him. You women are all for young flighty fellows, without considering that those people are never content with one mistress, but are roving always from one to another, as you have found by experience. Their greatest happiness is in gaining favours from you, and their utmost glory is to publish them. Truly, you think your love is all a secret, and that nobody but your maid and I were ever acquainted with it, whilst his neighbourhood and yours both talked of nothing else; but

it generally happens, that the persons concerned are the last that hear of such things. Therefore, if you have made a bad choice, keep to it, and leave me, whom you have despised, to another lady whom I have made choice of, one of more account than yourself, and who knows better how to distinguish people. As to my being concerned for your death, if you please, you may make the experiment. But, as I suppose you will scarcely humour me so far, so I now tell you, that if the sun begins to scorch, you may call to mind the cold you made me endure, and together they will make a proper temperature."

The disconsolate lady, seeing that all these words tended to some cruel purpose, began to weep again, and say, "Nay now, if nothing can move you to pity that concerns myself, yet let your love for that lady whom you say you have met with, who is wiser than I, and by whom you say you are beloved; let your regard, I say, for her, prevail upon you to forgive me, and to bring me my clothes, that I may dress myself and go down." The scholar fell a laughing at this, and seeing that it was now about noon, he replied, "Truly, I know not how to say you nay, as you entreat me by that lady: then tell me where they are, and I will go for them, that you may come down." She was a little comforted at this, and directed him to the place where she had laid them; so he went away, and ordered his servant to keep strict watch that nobody came to her relief till his return; and in the meantime, he went to a friend's house, where he dined, and laid himself down to sleep.

The lady, conceiving some vain hopes of being released, had sat herself down in the utmost agony, getting to that corner of the wall in which there was the most shade, where she continued, sometimes thinking, and then again lamenting; this moment in hopes, and the next altogether in despair of his return with her clothes. At last, musing on one thing after another, being quite spent with grief, and having had no rest the night before, she dropped asleep. The sun was now in the meridian, darting all its force directly upon her naked and most delicate body, as also upon her head, so that it not only scorched all the skin that lay exposed, but cleft it little by little into chinks, and blistered it to that degree that it made her awake; when, finding herself perfectly roasted, and offering to turn about, it all seemed to rend asunder like a piece of burnt parchment, that has been kept upon the stretch. Besides all this, her head ached to that degree as if it would rive in pieces, which was no wonder. Moreover, the reflection of the heat against her feet was so strong, that she could get no rest any where, but kept crying, and moving from place to place. And, as there was no wind, the flies and hornets were constantly buzzing about her, striking their stings into the chinks of her flesh, and covering her over with wounds, whilst it was her whole employment to beat them off, still cursing herself, her lover, and the scholar. Being thus harassed by the heat, by insects, by hunger, but much more by thirst, and pierced to the heart by a thousand bitter reflections, she got up to see if any body was near, resolving, whoever was within call, to beg their assistance; but even this comfort her ill fortune had denied her. The labourers were all gone out of the fìelds, on account of the heat, though it happened that nobody had been at work thereabouts all that day, being employed in threshing their com at home, so that she heard nothing but the grasshoppers, and saw only the river Amo, which, by making her long for some of its water, instead of quenching, did but add to her thirst. She saw also pleasant groves, cool shades, and country-houses, which now made her trouble so much the greater.

What more can be said of this unhappy lady? She who the night before, could by the whiteness of her skin, dispel even the shade of night, was now all brown and spotted, so that she seemed the most unsightly creature that could be.While she was thus void of all hope, and expecting nothing but death, towards the middle of the afternoon the scholar happened to awake, when he called her to mind, and returned to the tower, sending the servant back, who was yet fasting, to get his dinner. As soon as she saw him, all weak and miserable as she was, she came and placed herself down by the battlements, and said, "Oh, sir, you are most unreasonably revenged; for if I made you freeze almost with cold, one night in my court, you have roasted and burnt me for a whole day upon this tower, where I have been at death's door with hunger and thirst; I conjure you, therefore, to come up, and bestow that death upon me, which my heart will not let me inflict upon myself, and which I most earnestly long for, to put an end to that pain which I can no longer endure; or, if you deny me this favour, do, pray, send me up a little water to wash my mouth, my tears not being sufficient, such is the drought and scorching that I feel." The scholar was sensible by her manner of speaking, how weak she was; he perceived, also, by what he saw of her body, how it was scorched and blistered; for that reason, therefore, as well as her entreaties, he began to have a little compassion, but said, "Vile woman! thou shalt never meet with thy death from my hands; from thy own thou mayest if thou wilt; and just so much water will I give thee, as thou gavest me fire in my extremity. This only grieves me that, whilst I was forced to lie in dung for my recovery, thou, nevertheless, will be cured with the coldness of perfumed rose-water; and though I was near losing both limbs and life, yet thou, when stripped of thy skin, wilt appear with fresh beauty, like a serpent just uncased." - "Alas!" quoth the lady, "may only my enemies gain charms in that manner! But you, more cruel than any savage beast, how could you bear to torture me as you have done? What could I have expected worse from you, had I put all your relations to death in the cruelest manner imaginable? What greater punishment could be thought of for a traitor, who had been the destruction of a whole city, than to be roasted in the sun, and then devoured by flies? and not to give me so much as a drop of water, whilst the vilest malefactors, when they are about to suffer, are not denied even wine. - Now I see you fixed in your barbarous resolution, nor any way moved with what I have suffered, I shall wait patiently for my death. The Lord have mercy on me, and look with a just eye on what you have done!"With these words she withdrew to the middle of the place, despairing of her life, and ready to faint away a thousand times with thirst, where she sat lamenting her condition.

It being now towards evening, the scholar, thinking she had suffered enough, made his servant take her clothes wrapped up in his cloak, and follow him to her house, where he found her maid sitting at the door, all sad and disconsolate for her mistress's long absence. "Pray, good woman," said he, "what has become of your mistress?" - "sir," she replied, "I do not know; I thought to have found her in bed this morning, where I saw her last night, but she is neither to be found there, nor any where else, nor do I know what has become of her. But can you give me any tidings of her?" - "I wish only," quoth he, "that thou hadst been along with her, that I might have taken the same revenge of thee that I have had of her. But depend upon it thou shalt never escape; I will so pay thee for what thou hast done, that thou shalt remember me every time thou shalt offer to put a trick upon any one." Then he said to the servant, "Give her the clothes, and tell her she may go for her mistress if she has a mind." The servant accordingly delivered them, with that message, and the girl, knowing them again, was afraid her mistress was murdered, and could scarcely help shrieking, nevertheless she made all the haste she could to the tower.

It happened that a labourer of the widow's had lost two of his hogs that day, and coming near to the tower, to look for them, just as the scholar was departed, he heard the complaints the poor creature was making, so he cried out, "Who makes that noise?" She immediately knew his voice, and called him by his name, saying, "Go, I pray, and desire my maid to come to me." The man then knew her, and said, "Alas! madam, who has brought you hither? Your maid has been looking for you all day long. But who could have thought of finding you in this place? Then he took the sides of the ladder, and placed them as they should be binding them about with osiers: and as he was doing this, the maid came, and being able to hold her tongue no longer, she wrung her hands, and fell a roaring out, "Dear madam, O, where are you?" Her mistress hearing her, replied, as well as she could, "Good girl, never stand crying, but make haste, and bring me my clothes." Comforted by the sound of her mistress's voice, the maid jumped upon the ladder before it was made quite secure, and by the man's help got upon the tower, when, seeing her lie naked there, burnt like a log of wood, and quite spent, she cried over her, as if she had been dead. But the lady desired her to be quiet, and dress her; and understanding from her that nobody knew where she was, but the persons who had brought the clothes to her, and the labourer that was below, she was a little comforted, and begged earnestly of them to keep the secret. The labourer now took her upon his back, as she had no strength to walk, and brought her down safely in that manner; whilst the girl, following after with less caution than was necessary, slipped her foot, and falling down the ladder, broke her thigh, which occasioned her to make a most grievous outcry. The man, after he had set his lady on the grass, went to see what was the matter with the maid, and finding that she had her thigh broke, he laid her down by the lady, who, seeing this addition to her misfortunes, and that the person from whom she expected most succour was disabled, began to lament afresh, and the man, unable to pacify her, fell a weeping likewise. It was now sunset, and rather than let her lie there till night, as the disconsolate lady would have wished, he took her to his own house, and brought two of his brothers and his wife back with him for the maid, whom they carried upon a table. Having given the lady some water to refresh her, and used all the kind comfortable words they could think of, the labourer carried her to his own chamber, and his wife gave her a little bread soaked in water, and undressed and put her to bed. It was then contrived that they should both be taken to Florence that night, and so they were.

On her return home, the lady, who was never at a loss for invention, cooked up an artful story, which was believed by her brothers and sisters, and almost every one else, viz., that it was all done by enchantment. Physicians were sent for, who, with a great deal of pain and trouble to her, and not without the loss of her whole skin several times over, cured her of a violent fever, and other accidents attending it; and they also set the girl's broken thigh. From that time Helena forgot her lover, and was more careful for the future, both in choosing a spark, and in making her sport. The scholar, also, hearing what had happened to the girl, thought he had had full revenge, and so no more was said about it. Thus the foolish lady was served for her wit and mockery, thinking to make a jest of a scholar, as if he had been a common person, never considering that most of them, I do not say all, have the devil, as they say, in a string. Then take care, ladies, how you play your tricks, but especially upon scholars.

[We are informed by some of the commentators on Boccaccio that the circumstances related in this story happened to the author himself, and that the widow is the same with the one introduced in his "Laberinto d'Amore." The unusual minuteness with which the tale is related gives some countenance to such an opinion. However this may be, it has evidently suggested the story in the "Diable Boiteux," of Patrice, whose mistress, Lucila, makes him remain a whole night in the street before her windows, on the false pretence that her brother, Don Gaspard, is in the house, and that her lover must wait till he departs.]