NOVEL X.

The marquis of Saluzzo, having been prevailed upon by his subjects to marry, in order to please himself in the affair, made choice of a countryman's daughter, oy whom he had two children, which he pretended to put to death. Afterwards, seeming as though he was weary of her, and had taken another, he had his own daughter brought home, as if he had espoused her, whilst his wife was sent away in a most distressed condition. At length, being convinced of her patience, he brought her home again, presented her children to her, who were now of considerable years, and ever afterwards loved and honoured her as his lady.

The king's long novel being concluded, which had all the appearance of pleasing, Dioneo, as the only person left to speak, began in this manner: - We seem today, most gracious ladies, to have had only to do with kings, soldans, and such-like people; therefore, that I may not be left too far behind, I intend to speak of a marquis, not with regard to anything noble and great, but rather monstrously vile and brutish, although it ended well at last: which, notwithstanding the event, I would yet advise nobody to imitate.

It is a long time ago, that, among the marquises of Saluzzo, the principal or head of the family was a youth, called Gualtieri, who, as he was a bachelor, spent his whole time in hawking and hunting, without any thought of ever being encumbered with a wife and children; in which respect, no doubt, he was very wise. But this being disagreeable to his subjects, they often pressed him to marry, to the end that he might neither die without an heir, nor they be left without a lord; offering themselves to provide such a lady for him, and of such a family, that they should have great hopes from her, and he reason enough to be satisfied. "Worthy friends," he replied, "you urge me to do a thing which I was fully resolved against, considering what a difficult matter it is to find a person of a suitable temper, with the great abundance everywhere of such as are otherwise, and how miserable also the man's life must be who is tied to a disagreeable woman. As to your getting at a woman's temper from her family, and so choosing one to please me, that seems quite a ridiculous fancy; for, besides the uncertainty with regard to their true fathers, how many daughters do we see resembling neither father nor mother? Nevertheless, as you are so fond of having me noosed, I will to be so. Therefore, that I may have nobody to blame but myself, should it happen amiss, I will make my own choice; and I protest, let me marry whom I will, that, unless you show her the respect that is due to her as my lady, you shall know, to your cost, how grievous it is to me to have taken a wife at your request, contrary to my own inclination.” The honest men replied, that they were well satisfied, provided he would but make the trial.

Now the marquis had taken a fancy, some time before, to the behaviour of a poor country girl, who lived in a village not far from his palace, and thinking that she might live comfortably enough with her, he determined, without seeking any farther, to marry her. Accordingly, he sent for her father, who was a very poor man, and acquainted him with it. Afterwards, he summoned all his subjects together, and said to them, “Gentlemen, it was and is your desire that I take a wife: I do it rather to please you, than out of any liking I have to matrimony. You know that you promised me to be satisfied, and to pay her due honour, whoever she is that I shall make choice of. The time is now come when I shall fulfil my promise to you, and I expect you to do the like to me: I have found a young woman in the neighbourhood after my own heart, whom I intend to espouse, and bring home in a very few days. Let it be your care, then, to do honour to my nuptials, and to respect her as your sovereign lady; so that I may be satisfied with the performance of your promise, even as you are with that of mine.” The people all declared themselves pleased, and promised to regard her in all things as their mistress. Afterwards they made preparations for a most noble feast, and the like did the prince, inviting all his relations, and the great lords in all parts and provinces about him: he had also most rich and costly robes made, shaped by a person that seemed to be of the same size with his intended spouse; and provided a girdle, ring, and fine coronet, with everything requisite for a bride. And when the day appointed was come, about the third hour he mounted his horse, attended by all his friends and vassals; and having everything in readiness, he said, “My lords and gentlemen, it is now time to go for my new spouse.”

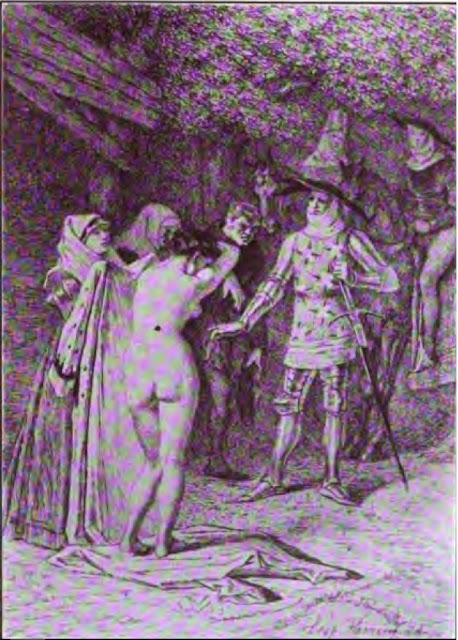

So on they rode to the village, and when he was come near the father's house, he saw her carrying some water from the well, in great haste, to go afterwards with some of her acquaintance to see the new marchioness; when he called her by her name, which was Griselda, and inquired where her father was. She modestly replied, “My gracious lord, he is in the house.” He then alighted from his horse, commanding them all to wait for him, and went alone into the cottage, where he found the father, who was called Giannucolo, and said to him, “Honest man, I am come to espouse thy daughter, but would first ask her some questions before thee.” He then inquired whether she would make it her study to please him, and not be uneasy at any time, whatever he should do or say; and whether she would always be obedient; with more to that purpose. To which she answered, “Yes.” He then led her out by the hand, and made her strip before them all; and ordering the rich apparel to be brought which he had provided, he had her clothed completely, and a coronet set upon her head, all disordered as her hair was; after which, every one being in amaze, he said, “Behold, this is the person whom I intend for my wife, provided she will accept of me for her husband.” Then, turning towards her, who stood quite abashed, “Will you,” said he, “have me for your husband?” She replied, “Yes, if it so please your lordship.” - “Well,” he replied, “and I take you for my wife.” So he espoused her in that public manner, and mounting her on a palfrey, conducted her honourably to his palace, celebrating the nuptials with as much pomp and grandeur as though he had been married to the daughter of the king of France; and the young bride showed apparently, that with her garments she had changed both her mind and behaviour. She had a most agreeable person, and was so amiable, and so good-natured withal, that she seemed rather a lord's daughter than a poor shepherd's; at which every one that knew her before was greatly surprised. She was so obedient also to her husband, and so obliging in all respects, that he thought himself the happiest man in the world; and to her subjects likewise so gracious and condescending, that they all honoured and loved her as their own lives, praying for her health and prosperity, and declaring contrary to their former opinion, that Gualtieri was the most prudent and sharp-sighted prince in the whole world; for that no one could have discerned such virtues under a mean habit, and a country disguise, but himself. In a very short time, her discreet behaviour and good works were the common subject of discourse, not in that country only, but everywhere else; and what had been objected to the prince with regard to his marrying her, now took a contrary turn. They had not lived long together, before she proved with child, and at length brought forth a daughter, for which he made great rejoicings.

But soon afterwards a new fancy came into his head, and that was to make trial of her patience by long and intolerable sufferings: so he began with harsh words, and an appearance of great uneasiness; telling her that his subjects were greatly displeased with her for her mean parentage, especially as they saw she bore children; and that they did nothing but murmur at the daughter already born. Which, when she heard, without changing countenance, or her resolution, in any respect, she replied, “My lord, pray dispose of me as you think most for your honour and happiness: I shall entirely acquiesce, knowing myself to be meaner than the meanest of the people, and that I was altogether unworthy of that dignity to which your favour was pleased to advance me.” This was very agreeable to the prince, seeing that she was no way elevated with the honour he had conferred upon her. Afterwards, having often told her, in general terms, that his subjects could not bear with the daughter that was born of her, he sent one of his servants, whom he had instructed what to do, who, with a very sorrowful countenance, said to her, “Madam, I must either lose my own life, or obey my lord's commands: now he has ordered me to take your daughter, and -“ without saying anything more. She, hearing these words, and noting the fellow's looks, remembering also what she had heard before from her lord, concluded that he had orders to destroy the child. So she took it out of the cradle, kissed it, and gave it her blessing; when, without changing countenance, though her heart throbbed with maternal affection, she tenderly laid it in the servant's arms, and said, “Take it, and do what thy lord and mine has commanded; but, prithee, leave it not to be devoured by the fowls or wild beasts, unless that be his will.” Taking the child, he acquainted the prince with what she said, who was greatly surprised at her constancy; and he sent the same person with it to a relation at Bologna, desiring her, without revealing whose child it was, to see it carefully brought up and educated. Afterwards the lady became with child a second time, and was delivered of a son, at which he was extremely pleased.

But, not satisfied with that he had already done, he began to grieve and persecute her still more; saying one day to her, seemingly much out of temper, “Since thou hast brought me this son, I am able to live no longer with my people; for they mutiny to that degree, that a poor shepherd's grandson is to succeed, and be their lord after me, that, unless I would run the risk of being driven out of my dominions, I must needs dispose of this child as I did the other; and then send thee away, in order to take a wife more suitable to me.” She heard this with a great deal of resignation, making only this reply: “My lord, study only your own ease and happiness, without the least care for me; for nothing is agreeable to me, but what is pleasing to yourself.” Not many days after, he sent for the son in the same manner as he had done for the daughter; and seeming also as if he had procured him to be destroyed, had him conveyed to Bologna, to be taken care of with the daughter. This she bore with the same resolution as before, at which the prince wondered greatly, declaring to himself, that no other woman was capable of doing the like. And, were it not that he had observed her extremely fond of her children, whilst that was agreeable to him, he should have thought it want of affection in her; but he saw it was only her entire obedience and condescension. The people, imagining that the children were both put to death, blamed him to the last degree, thinking him the most cruel and worst of men, and showing great compassion for the lady; who, whenever she was in company with the ladies of her acquaintance, and they condoled with her for her loss, would only say, “It was not my will, but his who begot them.”

But more years being now passed, and he resolving to make the last trial of her patience, declared, before many people, that he could no longer bear to keep Griselda as his wife, owning that he had done very foolishly, and like a young man, in marrying her, and that he meant to solicit the pope for a dispensation to take another, and send her away: for which he was much blamed by many worthy persons; but he said nothing in return, only that it should be so. She, hearing this, and expecting to go home to her father's, and possibly tend the cattle as she had done before; whilst she saw some other lady possessed of him, whom she dearly loved and honoured, was perhaps secretly grieved; but as she had withstood other strokes of fortune, so she determined resolutely to do now. Soon afterwards, Gualtieri had counterfeit letters come to him, as from Rome, acquainting all his people that his holiness thereby dispensed with this marrying another and turning away Griselda. He then had her brought before them, and said, “Woman, by the pope's leave I may dispose of thee, and take another wife. As my ancestors, then, have been all sovereign princes of this country, and thine only peasants, I intend to keep thee no longer, but to send thee back to thy father's cottage, with the same portion which thou broughtest me, and afterwards to make choice of one more suitable in quality to myself.” It was with the utmost difficulty she could now refrain from tears; and she replied, “My lord, I was always sensible that my servile condition would in no way accord with your high rank and descent. For what I have been, I own myself indebted to Providence and you; I consider it as a favour lent me: you are now pleased to demand it back; I therefore willingly restore it. Behold the ring with which you espoused me; I deliver it to you. You bid me take the dowry back which I brought you; you will have no need for a teller to count it, nor I for a purse to put it in, much less a sumpter-horse to carry it away; for I have not forgotten that you took me naked; and if you think it decent to expose that body, which has borne you two children, in that manner, I am contented; but I would entreat you, as a recompense for my virginity, which I brought you, and do not carry away, that you would please to let me have one shift over and above my dowry.” He, though ready to weep, yet put on a sterr countenance, and said, “Thou shalt have one only then.” And, notwithstanding the people all desired that she might have an old gown, to keep her body from shame, who had been his wife thirteen years and upwards, yet it was all in vain; so she left his palace in that manner, and returned weeping to her father's to the great grief of all who saw her. The poor man, never supposing that the prince would keep her long as his wife, and expecting this thing to happen every day, had safely laid up the garments of which she had been despoiled the day he espoused her. He now brought them to her, and she put them on, and went as usual about her father's little household affairs, bearing this fierce trial of adverse fortune with the greatest courage imaginable. The prince then gave it out that he was to espouse a daughter of one of the counts of Panago; and, seeming as if he made great preparations for his nuptials, he sent for Griselda to come to hom, and said to her, “I am going to bring this lady home whom I have just married, and intend to show her all possible respect at her first coming: thou knowest that I have no women with me able to set out the rooms, and do many other things which are requisite on so solemn an occasion. As, therefore, thou art best acquainted with the state of the house, I would have thee make such provisions as thou shalt judge proper, and invite what ladies thou wilt, even as though thou wert mistress of the house, and when the marriage is ended, get thee home to thy father's again. Though these words pierced like daggers to the heart of Griselda, who was unable to part with her love for the prince so easily as she had done her great fortune; yet she replied, “My lord, I am ready to fulfil all your commands.” She then went in her coarse attire into the palace, whence she had but just before departed in her shift, and with her own hands did she begin to sweep, and set all the rooms to rights, cleaning the stools and benches in the hall like the meanest servant, and directing what was to be done in the kitchen, never giving over till everything was in order, and as it ought to be. After this was done, she invited, in the prince's name, all the ladies in the country to come to the feast. And on the day appointed for the marriage, meanly clad as she was, she received them in the most genteel and cheerful manner imaginable.

Now Gualtieri, who had his children carefully brought up at Bologna (the girl being about twelve years old, and one of the prettiest creatures that ever was seen, and the boy six), had sent to his kinswoman there, to desire she would bring them, with an honourable retinue, to Saluzzo; giving it out all the way she came, that she was bringing the young lady to be married to him, without letting any one know to the contrary. Accordingly they all three set forwards, attended by a goodly train of gentry, and, after some days travelling, reached Saluzzo about dinner-time, when they found the whole country assembled, waiting to see their new lady. The young lady was most graciously received by all the women present, and being come into the hall where the tables were all covered, Griselda, meanly dressed as she was, went cheerfully to meet her, saying, “Your ladyship is most kindly welcome.” The ladies, who had greatly importuned the prince, though to no purpose, to let Griselda be in a room by herself, or else that she might have some of her own clothes, and not appear before strangers in that manner, were now seated, and going to be served round, whilst the young lady was universally admired, and every one said that the prince had made a good change; but Griselda, in particular, highly commended both her and her brother. The marquis now thinking that he had seen enough with regard to his wife's patience, and perceiving that in all her trials she was still the same, being persuaded, likewise, that this proceeded from no want of understanding in her, because he knew her to be singularly prudent, he thought it time to take her from that anguish which he supposed she might conceal under her firm and constant deportment. So, making her come before all the company, he said, with a smile, “What thinkest thou, Griselda, of my bride?” - “My lord,” she replied, “I like her extremely well; and if she be as prudent as she is fair, you may be the happiest man in the world with her: but I most humbly beg that you would not take those heart-breaking measures with this lady as you did with your last wife, because she is young, and has been tenderly educated, whereas the other was inured to hardships from a child.”

Gualtieri perceiving that though Griselda thought that person was to be his wife, that she nevertheless answered him with great humility and sweetness of temper, he made her sit down by him, and said, “Griselda, it is now time for you to reap the fruit of your long patience, and that they who have reputed me to be cruel, unjust, and a monster in nature, may know that what I have done has been all along with a view to teach you how to behave as a wife; to show them how to choose and keep a wife; and, lastly, to secure my own ease and quiet as long as we live together, which I was apprehensive might have been endangered by my marrying. Therefore, I had a mind to prove you by harsh and injurious treatment; and not being sensible that you have ever transgressed my will, either in word or deed, I now seem to have met with that happiness I desired. I intend, then, to restore in one hour what I had taken away from you in many, and to make you the sweetest recompense for the many bitter pangs I have caused you to suffer. Accept, therefore, this young lady, whom you thought my spouse, and her brother, as your children and mine. They are the same whom you and many others believed that I had been the means of cruelly murdering: and I am your husband, who love and value you above all things; assuring myself, that no person in the world can be happier in a wife that I am.” With this he embraced her most affectionately, when, rising up together (she weeping for joy), they went where their daughter was sitting, quite astonished with these things, and tenderly saluted both her and her brother, undeceiving them and the whole company. At this the women all arose, overjoyed, from the tables, and taking Griselda into the chamber, they clothed her with her own noble apparel, and as a marchioness, resembling such an one even in rags, and brought her into the hall. And being extremely rejoiced with her son and daughter, and every one expressing the utmost satisfaction at what had come to pass, the feasting was prolonged many days. The marquis was judged a very wise man, though abundantly too severe, and the trial of this lady most intolerable; but as for Griselda, she was beyond compare. In a few days the Count da Pagano returned to Bologna, and the marquis took Giannucolo from his drudgery, and maintained him as his father-in-law, and so he lived very comfortably to a good old age. Gualtieri afterwards married his daughter to one of equal nobility, continuing the rest of his life with Griselda, and showing her all the respect and honour that was possible. What can we say then, but that divine spirits may descend from heaven into the meanest cottages; whilst royal palaces shall produce such as seem rather adapted to have the care of hogs, than the government of men? Who but Griselda could, not only without a tear, but even with seeming satisfaction, undergo the most rigid and unheard-of trials by her husband? Many women there are, who, if turned out of doors naked in that manner, would have procured themselves fine clothes, adorning at once their persons and their husband's brows.

[The original of this tale was at one time believed to have been an old MS. Entitled “Le Parement des Dames”. This was first asserted by Duchat, in his notes on Rabelais. It was afterwards mentioned by Le Grand and Manni, and through them by the Abbé de Sade and Gallaud (“Discours sur quelques anciens Poètes”); but Tyrwhitt informs us, that Oliver de la Marche, the author of the “Parement des Dames,” was not born for many years after the composition of the “Decameron,” so that some other original must be sought. Noguier in his “Histoire de Thoulouse,” asserts that the patient heroine of the tale actually existed in 1103. In the “Annales d'Aquitaine,” she is said to have flourished in 1025. That there was such a person is positively asserted by Foresti de Beigamo, in his “Chronicle,” though he does not fix the period at which she lived. The probability, therefore, is that Boccaccio's novel, as well as the “Parement des Dames,” has been founded on some real or traditional incident; a conjecture which is confirmed by the letter of Petrarch to Boccaccio, written after a perusal of the “Decameron,” in which he says he had heard the story of Griselda related many years before.

From whatever source derived, “Griselda” appears to have been the most popular of all the stories of the “Decameron.” In the fourteenth century, the prose translations of it in French were very numerous; Le Grand mentions that he had seen upwards of twenty, under the different names, “Miroir des Dames,” (NE: L'espill, Jaume Roig, llibre de les dones, XV century, llengua valenciana) “Exemples de bonnes et mauvaises Femmes.” etc. Petrarch, who had not seen the “Decameron” till a short time before his death (which shows that Boccaccio was ashamed of the work), read it with much admiration, as appears from his letter, and translated it into Latin, in 1373. Chaucer, who borrowed the story from Petrarch, assigns it to the Clerk of Oxenforde, in his “Canterbury Tales.” The clerk declares in his prologue that he learned it from Petrarch at Padua; and if we may believe Warton, Chaucer, when in Italy, actually heard the story related by Petrarch, who, before translating it into Latin, had got it by heart, in order to repeat it ti his friends. The tale became so popular in France, that the comedians of Paris represented, in 1393, a Mystery, in French verse, entitled “Le Mystère de Griseldi.” There is also an English drama, named “Patient Grissel,” entered in Stationer's Hall, 1599. One of Goldoni's plays, in which the tyrant husband is king of Thessaly, is also formed on the subject of “Griselda.” In a novel by Luigi Alamanni, a count of Barcelona subjects his wife to a similar trial of patience with that which Griselda experienced. He proceeds, however, so far as to force her to commit dishonorable actions at his command. The experiment, too, is not intended as a test of his wife's obedience, but as a revenge, on account of her once having refused him as a husband.

The story of Boccaccio seems hardly deserving of so much popularity and imitation.

“An English reader,” says Ellis, in his notes to Way's Fabliaux,” is naturally led to compare it with our national ballad, the “Nut Brown Maid” (the “Henry and Emma” of Prior), because both compositions were intended to describe a perfect female character, exposed to severest trials, submitting, without a murmur, to unmerited cruelty, disarming a tormenter by gentleness and patience; and finally recompensed for her virtues by transports rendered more exquisite by her sufferings.” The author then proceeds to show that although the intention be the same, the conduct of the ballad is superior to that of the novel. “In the former, the cruel scrutiny of the feelings is suggested by the jealousy of a lover, anxious to explore the whole extent of his empire over the heart of a mistress; his doubts are perhaps natural, and he is only culpable because he consents to purchase the assurance of his own happiness at the expense of the temporary anguish and apparent degradation of the object of his affections. But she is prepared for the exertion of her firmness by slow degrees; she is strengthened by passion, by the consciousness of the desperate step she had already taken, and by the conviction that every sacrifice was tolerable which ensured her claim to the gratitude of her lover, and was paid as the price of his happiness; her trial is short, and her recompense is permanent. For his doubts and jealousy she perhaps found an excuse in her own heart; and in the moment of her final exultation and triumph in the consciousness of her own excellence, and the prospect of unclouded security, she might easily forgive her lover for having evinced that the idol of his heart was fully deserving of his adoration. Gualtieri, on the contrary, is neither blinded by love nor tormented by jealousy: he merely wishes to gratify a childish curiosity, by discovering how far conjugal obedience can be carried; and the recompense of unexampled patience is a mere permission to wear a coronet without further molestation. Nor, as in the ballad, is security by a momentary uneasiness, but by long years of suffering. It may be doubted whether the emotions to which the story of Boccaccio gives rise are at all different from those which would be excited by an execution on the rack. The spirit, too, of resignation, depends much on its motive; and the cause of morality is not greatly promoted by bestowing on a passive submission to capricious tyranny the commendation which is only due to a humble acquiescence in the just dispensations of Providence.”]

Dioneo's novel, which was now concluded, was much canvassed by the whole company, this blaming one thing, and that commending another, according to their respective fancies; when the king, seeing the sun was now far in the west, and that the evening drew on apace, said, without rising from his seat, “I suppose you all know, ladies, that a person's sense and understanding consist, not only in remembering things past, or knowing the present but that to be able, by both these means, to foresee what is to come, is, by the more knowing part of mankind, judged the greatest proof of wisdom. Tomorrow, you are aware, it will have been fifteen days since we, by way of amusement, and for the preservation of our lives, came out of Florence, avoiding all those cares and melancholy reflections which continually haunted us in the city, since the beginning of that fatal pestilence. And, in my opinion, we have done honestly and well. For, though some light things have been talked of, and a loose given to all sorts of innocent mirth, yet am I not conscious of anything blame-worthy that has passed among us; but everything has been decent, everything harmonious, and such as might well beseem the community of brothers and sisters. Lest, therefore, something should happen, which might give us uneasiness, and make people put a bad construction upon our being so long together, now all have had their days, and their shares of honour, which at present rests in me, I hold it most advisable for us to return from whence we came. Besides, as people know of our being together, our company may probably increase, which would make it entirely disagreeable. If you approve of it, then, I will keep the power till tomorrow that we depart; but if you resolve otherwise, I have a person in my eye to succeed me”. This occasioned great debates, but at last it was thought safest and best to comply with the king's advice. He consequently called the master of the household, and after giving proper directions for the next morning, dismissed them all till supper-time. They now betook themselves, as usual, some to one thing and some to another, for their amusement; and, when the hour came, supped very agreeably together, after which they began their music; and whilst Lauretta led up a dance, the king ordered Fiametta to sing a song, which she did in a pretty, easy manner, as follows: -

SONG.

CHORUS.

Did love no jealous cares infest,

No nymph on earth would be so blest.

If sprightliness, and blooming youth,

An easy and polite address,

Strict honour, and regard for truth,

Are charms which may command success;

Then sure you will my choice approve,

For these all centre in my love.

Did love, etc.

But when I see that arts are tried,

By nymphs as fair and wise as I,

A thousand fears ma heart betide,

Lest they should rob me of my joy;

Thus that for which I triumph'd so,

Becomes the cause of all my woe.

Did love, etc.

Would he prove firm to my desire,

No more I should myself perplex:

But virtues like to his inspire

The same regard in all our sex:

This makes me dread what nymph be nigh,

And watch each motion of his eye.

Did love, etc.

Hence, then, ye damsels, I implore,

As you regard what's just and fit,

That you, by am'rous wiles, no more

This outrage on my love commit:

For know, whilst thus you make me grieve,

You shall repent the pain you give.

Did love no jealous cares infest,

No nymph on earth would be so blest.

As soon as Fiammetta had finished her song, Dioneo, who sat close to her, laughed and said, “Madam, it would be kind to let the ladies know whom you mean, for fear some other should take possession out of ignorance, and you have cause to be offended.”

The song was followed by many others, and, it now drawing near midnight, they all went, at the king's command, to repose themselves. By break of day they arose, and, the master of the household having sent away their carriages, returned, under the conduct of their discreet king, to Florence, when the three gentlemen left the seven ladies in new St. Mary's church, where they first met, going from thence where it was most agreeable to themselves; and the ladies, when they thought fit, repaired to their several houses.

THE END.