NOVEL IX.

Federigo being in love, without meeting with any return, spends all his substance, having nothing left but one poor hawk, which he gives to his lady for her dinner when she comes to his house; she, knowing this, changes her resolution, and marries him, by which means he becomes very rich.

The queen now observing that only she and Dioneo were left to speak, said pleasantly to this effect: - As it is now come to my turn, I shall give you, ladies, a novel something like the preceding one, that you may not only know what influence the power of your charms has over a generous heart, but that you may learn likewise to bestow your favours of your own accord, and where you think most proper, without suffering Fortune to be your directress, who disposes blindly, and without the least judgment whatsoever.

You must understand then, that Coppo di Borghese (who was a person of great respect and authority among us, and whose amiable qualities, joined to his noble birth, had rendered him worthy of immortal fame) in the decline of life, used to divert himself among his neighbours and acquaintances, by relating things that had happened in his day, and this he knew how to do with more exactness and elegance of expression than any other person: he, I say, amongst other pleasant stories, used to tell us, that at Florence dwelt a young gentleman named Federigo, son of Filippo Alberighi, who, in feats of arms and gentility, surpassed all the youth in Tuscany. This gentleman was in love with a lady called Monna Giovanna, one of the most agreeable women in Florence, and to gain her affection, he was continually making tilts, balls, and such diversions; lavishing away his money in rich presents, and everything that was extravagant. But she, as pure in conduct as she was fair, made no account either of what he did for her sake, or of himself.

As Federigo continued to live in this manner, spending profusely, and acquiring nothing, his wealth soon began to waste, till at last he had nothing left but a very small farm, the income of which was a most slender maintenance, and a single hawk, one of the best in the world. Yet loving still more than ever, and finding he could subsist no longer in the city, in the manner he would choose to live, he retired to his farm, where he went out fowling, as often as the weather would permit, and bore his distress patiently, without ever making his necessity known to anybody. Now it happened, after he was thus brought low, the lady's husband fell sick, and, being very rich, he made a will, by which he left all his substance to an only son, who was almost grown up, and if he should die without issue, he then ordered that it should revert to his lady, whom he was extremely fond of; and when he had disposed thus of his fortune, he died. Monna Giovanna now, being left a widow, retired, as our ladies usually do during the summer season, to a house of hers in the country, near to that of Federigo: whence it happened that her son soon became acquainted with him, and they used to divert themselves together with dogs and hawks; and the boy, having often seen Federigo's hawk fly, and being strangely taken with it, was desirous of having it, though the other valued it to that degree, that he knew not how to ask for it.

This being so, the boy soon fell sick, which gave his mother great concern, as he was her only child, and she ceased not to attend on and comfort him; often requesting, if there was any particular thing which he fancied, to let her know it, and promising to procure it for him if it was possible. The young gentleman, after many offers of this kind, at last said, "Madam, if you could contrive for me to have Federigo's hawk, I should soon be well." She was in some perplexity at this, and began to consider how best to act.

She knew that Federigo had long entertained a liking for her, without the least encouragement on her part; therefore she said to herself, "How can I send or go to ask for this hawk, which I hear is the very best of the kind, and which is all he has in the world to maintain him,? Or how can I offer to take away from a gentleman all the pleasure that he has in life?" Being in this perplexity, though she was very sure of having it for a word, she stood without making any reply; till at last the love of her son so far prevailed, that she resolved at all events to make him easy, and not send, but go herself. She then replied, “set your heart at rest, my boy, and think only of your recovery; for I promise you that I will go tomorrow for it the first thing I do." This afforded him such joy, that he immediately shewed signs of amendment.

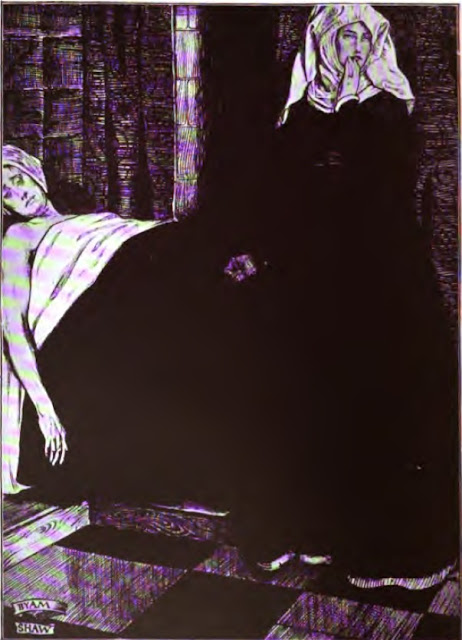

The next morning she went, by way of a walk, with another lady in company, to Federigo's little cottage to inquire for bim. At that time, as it was too early to go out upon his diversion, he was at work in his garden. Hearing, therefore, that his mistress inquired for him at the door, he ran thither, surprised and full of joy; whilst she, with a great deal of complaisance, went to meet him; and, after the usual compliments, she said, "Good morning to you, sir; I am come to make you some amends for the losses you have sustained on my account; what I mean is, that I have brought a companion to take a neighbourly dinner with you today." He replied, with a great deal of humility, "Madam, I do not remember ever to have suffered any loss by your means, but rather so much good, that if I was worth anything at any time it was due to your singular merit, and the love I had for you: and most assuredly this courteous visit is more welcome to me than if I had all that I have wasted returned to me to spend over again; but you are come to a very poor host." With these words he shewed her into his house, seeming much out of countenance, and thence they went into the garden, when, having no company for her, he said, "Madam, as I have nobody else, please to admit this honest woman, a labourer's wife, to be with you, whilst I set forth the table."

Although his poverty was extreme, never till now had he been so sensible of his past extravagance; but finding nothing to entertain the lady with, for whose sake he had treated thousands, he was in the utmost perplexity, cursing his evil fortune, and running up and down like one out of his wits. At length, having neither money nor anything he could pawn, and longing to give her something, at the same time that he would not make his case known, even so much as to his own labourer, he espied his hawk upon the perch, seized it, and finding it very fat, judged it might make a dish not unworthy of such a lady. Without farther thought, then, he wrung its head off, and gave it to a girl to dress and roast carefully, whilst he laid the cloth, having a small quantity of linen yet left; and then he returned, with a smile on his countenance, into the garden to tell Monna Giovanna that what little dinner he was able to provide was now ready. She and her friend, therefore, entered and sat down with him, he serving them all the time with great respect, when they ate the good hawk, not knowing what it was.

After dinner was over, and they had sat chatting a little while together, the lady thought it a fit time to tell her errand, and addressed him courteously in this manner:

- “Sir, if you call to mind your past life, and my resolution, which perhaps you may call cruelty, I doubt not but you will wonder at my presumption, when you know what I am come for: but if you had children of your own, to know how strong our natural affection is towards them, I am very sure you would excuse me. Now, my having a son forces me, against my own inclination, and all reason whatsoever, to request a thing of you, which I know you value extremely, as you have no other comfort or diversion left you in your small circumstances; I mean your hawk, which he has taken such a fancy to, that unless I bring it back with me, I very much fear that he will die of his disorder. Therefore I entreat you, not for any regard you have for me (for in that respect you are in no way obliged to me), but for that generosity with which you have always distinguished yourself, that you would please to let me have it, so that I may be able to say that my child's life has been restored to me through your gift, and that he and I are under perpetual obligations to you."

Federigo, hearing the lady's request, and knowing it was out of his power to fulfil it, began to weep before he was able to make a word of reply. This she at first attributed to his reluctance to part with his favourite bird, and expected that he was going to give her a flat denial; but after she had waited a little for his answer, he said, "Madam, ever since I have fixed my affections upon you, fortune has still been contrary to me in many things, and sorely I have felt them; but all the rest is nothing to what has now come to pass. You are here to visit me in this my poor dwelling, to which in my prosperity you would never deign to come; you also entreat a small present from me, which it is wholly out of my power to give, as I am going briefly to tell you. As soon as I was acquainted with the great favour you designed me, I thought it proper, considering your superior merit and excellency, to treat you, according to my ability, with something choicer than is usually given to other persons, when, calling to mind my hawk, which you now request, and his goodness, I judged him a fit repast for you, and you have had him roasted. Nor could I have thought him better bestowed, had you not now desired him in a different manner, which is such a grief to me, that I shall never be at peace as long as I live: "and saying this, he produced the hawk's feathers, feet, and talons. The lady began now to blame him for killing such a bird to entertain any woman with, in her heart all the while extolling the greatness of his soul which poverty had no power to abase.

Having now no further hopes of obtaining the hawk, she took leave of Federigo, and returned sadly to her son; who, either out of grief for the disappointment, or through the violence of his disorder, died in a few days. She continued sorrowful for some time; but being left rich, and young, her brothers were very pressing with her to marry again. This went against her inclination, but finding them still importunate, and remembering Federigo's great worth, and the late instance of his generosity, in killing such a bird for her entertainment, she said, "I should rather choose to continue as I am; but since it is your desire that I take a husband, I will have none but Federigo de gli Alberighi." They smiled contemptuously at this, and said, "You simple woman! what are you talking of? He is not worth one farthing in the world." She replied, "I believe it, brothers, to be as you say; but know, that I would sooner have a man that stands in need of riches, than riches without a man." They hearing her resolution, and well knowing his generous temper, gave her to him with all her wealth; and he, seeing himself possessed of a lady whom he had so dearly loved, and of such a vast fortune, lived in all true happiness with her, and was a better manager of his affairs than he had been before.

[This is the "Faucon,” of La Fontaine. Of this story it has been remarked, that "as a picture of the habitual workings of some one powerful feeling, where the heart reposes almost entirely on itself, without the violent excitement of opposing duties or untoward circumstances, nothing ever came up to the story of Frederico and his Falcon. The perseverance in attachment, the spirit of gallantry and generosity displayed in it, has no parallel in the history of heroical sacrifices. The feeling is so unconscious too, and involuntary, is brought out in such small, unlooked-for, and unostentatious circumstances, as to show it to have been woven into the very nature and soul of the author." ]