NOVEL X.

Pietro di Vinciolo goes to sup at a friend's house; his wife, in the meantime, has her gallant: Pietro returns, when she hides him under a chicken coop. Pietro relates, that a young fellow was found in Ercolano's house, where he supped, who had been concealed by his wife. Pietro's wife blames very much the wife of Ercolano: meanwhile an ass happening to tread on the young man's fingers who lay hidden, he cries out. Pietro runs to see what is the matter, and finds out the trick. At length they make it up.

The queen had now made an end, and every one was pleased with Federigo's good fortune, when Dioneo thus began: - I know not whether I should term it a vice, accidental, and owing to the depravity of our manners; or whether it be not rather a national infirmity, to laugh sooner at bad things than those which are good, especially when they no way concern ourselves. Therefore, as the pains which I have before taken, and am also now to undergo, aim at no other end but to drive away melancholy, and to afford matter for mirth and laughter, although, charming ladies, some part of the following novel be not altogether so modest, yet, as it may make you merry, I shall venture to relate it. You may do in this case, as when you walk in a garden, that is, pick the roses, and leave the briars behind you. Just so you may leave the vile fellow to his own evil reflections, and laugh at the amorous wiles of his wife, having that regard for other people's misfortunes which they deserve.

There dwelt not long since in Perugia, a very rich man, named Pietro di Vinciolo, who took to him a wife, more, perhaps, to deceive people, and diminish the bad opinion of him universally entertained in Perugia, than for anything else. Fortune was so far conformable to his inclinations, that the wife he found was a young, buxom, red-haired woman, who required two husbands rather than one. Consequently, they had continual jars and animosities together, whilst she would often argue with herself in this way:

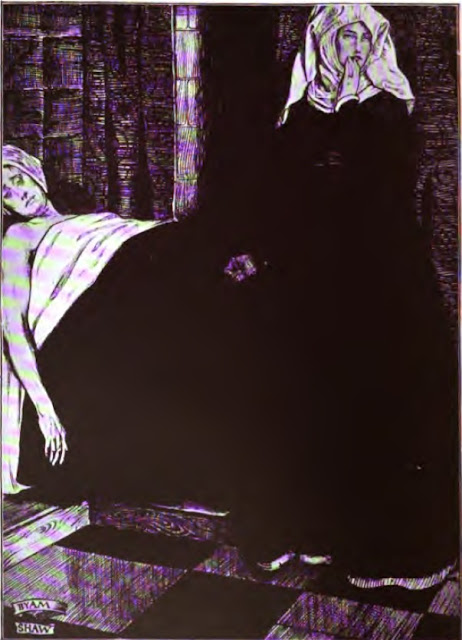

"This wretch abandons me to follow his infamous propensities. I made choice of him for a husband, and brought him a good fortune, knowing he was a man, and supposing he was fond of what men ought to be fond of. If I had thought he was not a man I would never have had him. He knew I was a woman; why did he take me for his wife if he disliked women? This is not to be borne. Had I been disposed to renounce the world, I would have shut myself up in a nunnery at once. I shall have old age overtake me before I know one good day, and then it will be too late to expect it." Full of such reflections as these, and resolved to indemnify herself for her husband's neglect, she went at last and made her case known to a sanctified old crone, who was perpetually saying over her Pater Nosters, and would talk of nothing else but the lives of the holy fathers, and the wounds of St. Francis.

"My daughter," said the old woman, when the lady had made known her grievances, and her intention of providing a remedy for them, "the Lord knows you will do quite right; and if it was for nothing else, you and every young woman ought to do the same in order not to lose the good time of youth; for there is no sorer grief to any one of right understanding, than to have wasted precious time. When we are grown old what the devil are we good for, but to sit in the chimney corner, and keep the fire warm? If there's ne'er another can bear true testimony to this, at least I can; for never can I think, without bitter anguish of spirit, on the time I let slip without profit. I did not lose it all, mind; I would not have you suppose I was such a ninny; but I did not get all the good out of it I might. When I call this to mind, and that I am now come to be what you see me, with never a chance of any one giving me a spark of fire to light my tinder, God knows what a heart's grief it is to me. It is not so with men; they are born good for a great many things besides this we are talking of, and the greater part of them are more esteemed in their old age than when they are young. But women are good for nothing but to bear children, or to be made use of to get them, and it is for that they are courted. If you want anything to make this clear to you, you have only to consider that women are always ready, but the men are not; besides, one woman can give enough to do to many men, but several men could not cloy one woman. Since then we are born for this, I say again that you will do quite right to give your husband tit-for-tat, so that when you grow old your soul may have no cause to upbraid your body. In this world everybody gets what he helps himself to, and no more, and this is especially the case with women, who have much more reason than men to make good use of their time while they may; for when we grow old neither our husbands, nor any one else, will look upon us, but they send us into the kitchen to talk to the cat, and count the pots and pans. Nay, what is worse they make rhymes upon us, and jibe us, saying, "Tit bits for the young, refuse for the old." The long and the short of the matter, my dear, is this: you could not have made choice of a fitter person than myself to open your mind to, or one that knows better how to help you. There is not the proudest man that wears a head, but I dare tell my mind to, nor the stubbornest, and most uncivil, but I can make fain to follow my leading. Let me only know who it is that best pleases you, and leave the rest to me. But there is one thing, my dear, I would beg you to bear in mind, that is, that I am a poor body, and I would have you partake the benefit of all my pardons and Pater Nosters."

It was then agreed that if the old woman should meet a certain gentleman in the street, whom the lady described to her, she should know what to do; and, upon this, the lady gave her a piece of salt meat, and sent her away. In a short time the old woman secretly brought her the person she desired, and others afterwards from time to time, according to the lady's fancy, which was a very lively one, and which she gratified as diligently as the fear in which she stood of her husband would allow her. One evening it happened that Pietro being engaged to sup with a friend of his, called Ercolano, the lady made the old woman bring her one of the handsomest and most engaging striplings in all Perugia; but she and her gallant were no sooner seated at table, than Pietro was heard knocking at the door. She was frightened out of her wits, and wishing to hide the youth somewhere or other, and not knowing where to put him better, she covered him with a hen-coop, which stood in a porch adjoining the supper-room, and throwing an empty sack over it, ran to open the door, saying, "Why husband, you have soon made an end of your supper." - "I have not tasted one morsel." - "How comes that?" -"I will tell you," said Pietro, "how it was."

"Ercolano, his wife, and myself, were all sat down, when he heard somebody sneeze; this we did not regard for once or twice, but when it happened three, four, or five times, it naturally surprised us: and Ercolano (who was vexed that his wife had made him wait some time at the door before she let him in) said, in a passion, "What is the meaning of this? Who is it that sneezes in this manner?" And getting up from the table, he went towards the stairs, under which was a cupboard, made to set things out of the way, and supposing the sound come thence, he opened the door, when there immediately issued out the greatest stench of sulphur that could be, though we had perceived something of it before.

Ercolano and his wife had some words about it; when she told him that she had been whitening her veils with brimstone, and had set the pan, over which she had laid them to receive the steam, in that place, and she supposed it continued yet to smoke. After he had opened the door, and the smoke was a little dispersed, he espied the sneezer, who was still hard at it under the pungent influence of the sulphur; but though he continued sneezing, yet he was so near suffocation, that in a very little time more, he would neither have done that, nor anything else. Ercolano, seeing the person at last, cried out, “so, madam! I now see why you made us wait so long at the door, but let me die if I do not pay you as you deserve." The wife, finding that she was discovered, rose from the table without making any excuse, and went I know not whither. Ercolano, not perceiving that his wife was fled, called upon the man that sneezed, and ordered him to come out; but, notwithstanding all he could say, the other never offered to stir, nor indeed was he able. Ercolano at last drew him out by the foot, and was running for a knife to kill him, but I, fearing to be drawn into some difficulty myself about it, would not suffer him to put the fellow to death; but defended him, and called out to the neighbours, who came and carried him away. This spoiled our supper, and I have not had one bit, as I told you."

The lady hearing this account, saw that other women were of the same disposition with herself, although some proved more unlucky than others. She would gladly have vindicated Ercolano's wife, but that she thought by blaming the faults of other people, to make the way more open for her own; so she began: - "Here is a fine affair, truly! this is your virtuous and good woman, who seemed so spiritually-minded always, that I could have confessed myself to her upon occasion. What is worse, she is old: a fine example she sets to young people! Cursed be the hour of her birth, and herself also; vile woman as she is! to be a disgrace to her whole sex; to be so mindless of her own honour, and her plighted faith to her husband, as not to be ashamed to injure so deserving a person, and one who had been always so tender of her! As I hope for mercy, I would have none on such prostitutes, they should every soul of them be burnt alive." Now calling to mind her own spark who was concealed, she began to fondle her husband, and would have had him go to bed, but he, who had more stomach to eat than sleep, asked whether she had anything for supper. "Yes, truly," quoth she, "we are used to have suppers when you are from home. I should fare better were I Ercolano's wife, my dear; now do go to bed."

That evening it happened that some of Vinciolo's labourers had come with some things out of the country, and had put their asses, without giving them any water, into a stable near the porch. One of the asses slipped his halter, being very thirsty, and went smelling everywhere for drink, till he came to the coop under which the young man was hidden.

Now he was forced to lie flat on his belly, and one of his fìngers, by strange ill fortune, was uncovered, so that the ass trod upon it, which made him cry out most terribly. Pietro wondered to hear such clamour in the house, and fìnding it continued, the ass still squeezing the finger close, he called aloud, "Who is there?" Then running to the coop, and turning it up, he saw the young man, who, besides the great pain he had suffered, was frightened to death lest Pietro should do him some mischief. Pietro asked him what business he had there; to which he made no reply, but begged he would do him no harm. "Get up," said Pietro, "I shall not hurt you, only tell me how you came hither, and upon what account! " The young man confessed everything; whilst Pietro, full as glad that he had found him, as his wife was sorry, brought him into the room where she sat, in all the terror imaginable, expecting him. Seating himself now before her, he said, "Here, you that were so outrageous at Ercolano's wife, saying that she should be burnt, and that she was a scandal to you all; what do you say now of yourself? Or how could you have the assurance to utter such things with regard to her, when you knew yourself to be equally guilty? You are all alike, and think to cover your own transgressions by other people's mistakes: I wish a fire would come from heaven, and consume you altogether, for a perverse generation as you are." The lady, now seeing that he went no further than a few words, put a good face on the matter, and replied, "Yes, I make no doubt but you would have us all destroyed; for you are as fond of us as a dog of a stick. You do well to compare me to Ercolano's wife, who is an ugly, hypocritical old woman, and he one of the best of husbands, that gives her what she likes; whereas, you know it is the reverse with regard to us two; I would sooner go in rags, were you what you ought to be, than to have everything in plenty, and you continue the same person you have always been." Pietro found she had matter enough to serve her the whole night, and having no mind to hear more, said "Enough for the present, madam; I will take care that you shall have more comfort for the time to come; only do me the great favour to see and get us something for supper, for I suppose this young spark is fasting as well as myself." - "´Tis very true," she replied, "for we were going to sit down when you unluckily came to the door." - "Then go and get something," he said, "and after supper I will settle this matter in such a way as will leave you no cause for complaint." She, finding her husband was satisfied, went instantly about it, and they all three supped cheerfully together. What followed I cannot pretend to tell you, but it was said next day in Perugia that the husband was revenged in his own way, and the wife not displeased.

[The greater part of this tale is taken from the ninth book of the Golden Ass, of Apuleius. It also bears a strong resemblance to the thirty-first and thirty-third novels of Girolamo Morlini.]

If Dioneo's novel was not much laughed at by the ladies it was not for want of mirth, but from modesty. The queen, seeing that there was an end of the novels of her day, arose, and taking the crown from her own head, placed it upon Eliza's, saying, "Madam, now it is your business to command:" Eliza, taking upon herself the honour, gave the same orders to the master of the household, as had been done in the former reigns, with regard to what was necessary during her administration; she then said, "We have often heard that many people by their ready wit and smart repartees, have not only blunted the keen satire of other persons, but have also warded off some imminent danger. Then, as the subject is agreeable enough, and may be useful, I will that tomorrow's discourse be to that effect: namely, of such persons as have retorted some stroke of wit which was pointed at them; or else, by some quick reply, or prudent foresight, have avoided either danger, or derision." This was agreeable to the whole assembly, and the queen now gave them leave to depart till the hour of supper; at that time they were called together and sat cheerfully down as usual. When supper was over, Emilia was ordered to begin a dance, and Dioneo to sing. But he, attempting to sing what the queen disapproved, she said, with some warmth, "Dioneo, I will have none of this ribaldry; either sing us a song fit to be heard, or you shall see that I know how to resent it." At these words he put on a more serious countenance, and began the following

SONG.

Cupid, the charms that crown my fair,

Have made me slave to you and her.

The lightning of her eyes,

That darting through my bosom flies,

Doth still your sov'reign power declare.

At your control

Each grace binds fast my vanquish'd soul.

Devoted to your throne

From henceforth I myself confess.

Nor can I guess

If my desires to her be known;

Who claims each wish, each thought so far.

That all my peace depends on her.

Then haste, kind godhead, and inspire

A portion of your sacred fire;

To make her feel

That self-consuming zeal,

The cause of my decay,

That wastes my very heart away.

When Dioneo had made an end, the queen called for several other songs, but his, nevertheless, was highly commended; afterwards, great part of the evening being spent, and the heat of the day sufficiently damped by the breezes of the night, she ordered them all to go and repose themselves till the following day.