NOVEL III.

Master Simon, the doctor, with Bruno, and the rest, make Calandrino believe that he is with child. The patient gives them fowls and money, to compound a medicine for him, and he recovers without being delivered.

After Eliza had concluded her novel, and the company had all expressed their joy for the lady's happy escape from the invidious censures of her sister-nuns, the queen ordered Filostrato to proceed, which he immediately did in this manner: - The odd figure of a judge, that was spoken of yesterday, prevented my giving you a story of Calandrino, which I had ready to tell you. Therefore, as whatever is related of him must be entertaining, though we have had a great deal already about him and his companions, I shall now say what I had then in my mind.

You have heard who Calandrino was, as well as the rest of the people concerned in this novel; so I shall tell you, without farther preface, that he had an aunt who died and left him about twenty pounds, on which he began to talk of purchasing an estate, and was running to treat with every broker in Florence, as if he had been worth the Indies; but the negotiation always broke down when they come to talk of a price. Now Bruno and Buffalmacco, who knew all this, had often told him that he had better spend the money with them, than lay it out on a little paltry land; but in vain; he would never part with a farthing. One day, the two wags being in company with another painter, whose name was Nello, they all agreed to feast themselves well at Calandrino's expense, and settled how it was to be done. The next morning, as Calandrino was going out of his house, Nello met, and said, "Good morning to you, friend." - "The same to you," Calandrino replied, "and a good year also." Nello now stopped, and began to look wistfully in his face. "What are you looking at?'said Calandrino. "Has anything been the matter with you in the night?" quoth Nello. "You are quite a different person." Calandrino grew very thoughtful at this, and said, "Oh, dear me! do you think I am ill?" - "Oh! I do not say that," replied Nello, "though I never saw a man so altered, but it may be something else;"and away he went. Calandrino went on, a little diffident, though feeling nothing all the time, when Buffalmacco came up to him, seeing him part from Nello, and asked him whether he was well. Calandrino replied, "Indeed I do not know; is it possible to be otherwise, and I not perceive it?" - "It may be so, or it may not," said Buffalmacco, "but I assure you, you look as though you were half dead." He now thought himself in a high fever, when Bruno came up, and the first word he said was, "Why, Calandrino, how you look! you are like a ghost. What is the matter with you?" He now concluded it was really so, and asked, in a great fright, what he had best do. "I advise," quoth Bruno, "that you go home and get to bed, cover yourself up close, and send your water to Master Simon, the doctor: he is our friend, you know, and will tell you at once what to do; in the meantime we will go with you, and do what we can for you." So they took him to his own house, and he went up stairs ready to die away every moment, saying to his wife, "Come and cover me up well in bed, for I find myself extremely ill." Having laid down, he sent his water by a little girl to the doctor, whose shop was then in the old market, at the sign of the Melon. Bruno now said to his friends, "Do you stay here, and I will go and hear what the doctor says, and bring him with me if there be occasion." "Pray do, my good friend," said Calandrino, "and let me know how it stands with me, for I feel very strangely in my inside."

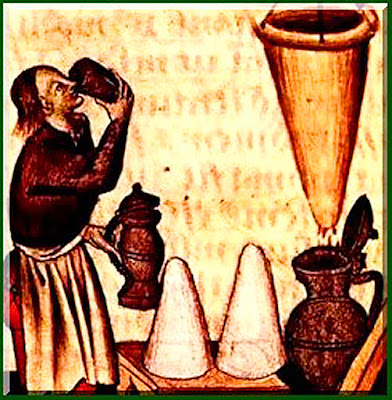

Bruno getting to the doctor's before the girl, let him into the secret. When she came there, and he had examined the water, he said to her, "Go, and bid him keep warm, and I will come instantly, and give directions what to do." She returned, and told Calandrino, and in a little time the doctor and Bruno came together, when the doctor sat down by him, and began to feel his pulse: at last he said, the wife being present, "I must tell you, as a friend, that your illness is nothing else but your being with child." As soon as Calandrino heard this, he began to roar out and say to his wife, "O, Tessa, this is all your doing, che non vuogali altro che di sopra (EN: that you don't want anything but to ride me; sopra: super: over). I told you how it would be." Poor Tessa, who was a very modest woman, was so overcome with shame at hearing her husband talk thus, that she left the room, without saying a word. Calandrino continued his lamentations, crying, O Lord! what shall I do? How shall I be delivered? Which way is the child to come into the world? It's a clear case, I am a dead man, for which I may thank my wife curse her! O that I were well! I would not leave a whole bone in her skin. If I have only the luck to get over it this time, I'll take care she does not get the upperhand of me again, let her beg as hard as she will." His companions had much ado to keep from laughing, seeing him in all this fright; and as for the doctor, he shewed all his teeth in such a manner, that you might have drawn every one of them. At length. Calandrino beseeching the physician's best advice and assistance, doctor Simon replied, "Calandrino, I would not have you make yourself too uneasy; for since I know your ailment, I doubt not but I shall soon give you relief, and with a very little trouble; but it will be with some expense." - "O doctor," quoth the patient, "I have twenty pounds, which should have bought me an estate: take it all, rather than let it come to a labour; for I hear the women make such a noise at those times, though they have so much room, that I shall never get through it alive." - " Never fear," said the doctor, "I shall prepare you a distilled liquor, very pleasant to the taste, which will dissolve and bring it away in three days, and leave you as sound as a trout. Now I must have six fat fowls, and for the other things, which will cost about ten shillings, you must give one of your friends here the money to buy, and bring them to my shop; and tomorrow morning I will send you the distilled water, which you must drink by a large glassful at a time." He replied, "Doctor, I rely upon you. So he gave Bruno ten shillings, and money also for the fowls, and desired he would take that trouble upon him.

The doctor made a little hippocrass, and sent it to him; whilst Bruno, with his companions and the doctor, were very merry over the fowls, and other good cheer purchased with the rest of the money. After Calandrino had drunk the hippocrass for the three mornings, the doctor came with his companions to see him, and said, after feeling his pulse, "You are now quite well, and need confine yourself within doors no longer." He was overjoyed at this, and gave the doctor great thanks, telling everybody he met what a cure Doctor Simon had wrought on him in three days' time, and without the least pain. Nor were his friends less pleased in overreaching his extreme avarice; but as to his wife, she saw into the tpck, and made a great clamour about it.